Bay View, Michigan, July 23, 2022

1. “A Song about You” (Gayden Wren, 2019).

A year or two back, I noticed that in 2020 a country singer named Sam Grow had premiered a song called “Song About You.” I haven’t heard it, so I don’t know if it’s anything like mine. For the record, I debuted mine during a show at the Manhattan club Don’t Tell Mama in July 2019; so, if one of us stole the song, it was him.

Probably not, though, because a lot of songwriters have specific other people to whom they return again and again in their songs, to the point of obsession. For Hank Williams, “you” was usually his first wife, Audrey Williams—according to his second wife, Billie Jean, he was driving with her when he was inspired to write a song … about Audrey. (Granted, that song was “Your Cheating Heart”; I didn’t say that it’s always love songs you write.) Creative people often tend to fixate: For Hank Williams Jr., it’s his father. For John Lennon it was Yoko Ono. For painter Andrew Wyeth, it was Christina Olson. Art is like that.

This song may or may not be about a particular person in my own life. It’s really about the phenomenon of coming back to another person again and again, trying to use your art to work out your relationship with him or her. It’s natural, if you think about it: Human beings use their thought processes to analyze their relationships, and for songwriters—or painters, poets, playwrights or whatever—creativity is the reflexive channel into which our thought processes flow. It’s more surprising, perhaps, when a creative person doesn’t use his or her art to explore those relationships.

The obvious answer song is “Not Another Song About Me”; maybe someone will write it sometime.

2. “Sounds Like Country from Here” (Gayden Wren, 2018).

What I play does sound like country to me, even if to many people it falls short of the Kristofferson Test: “If it sounds like country, man, that’s what it is. It’s a country song.” (Kristofferson is heard saying this at the beginning of his recording of “Me and Bobby McGee.”) This suggests that what makes a song country is its arrangement, with country instruments rather than, say, pop instruments or classical instruments.

Personally, I don’t buy this, because that would mean that any song can be a country song—for example, Ernest Tubb’s recording of “White Christmas”—if it’s played on country instruments or in a country style. I think there are certain themes, certain classic images and certain types of stories that have an innately country feel, and certain ones that don’t. I don’t care what band lineup you have, “Anything Goes” isn’t a country song.

More broadly, I’m not that interested in the question of what’s country and what isn’t. Americans love to classify their art into micro-genres (“That only sounds like neo-country folk, it’s actually Americana-flavored alt-gospel”), but the rest of the world doesn’t seem to find this a rewarding pastime, and I’m with them. Who cares if Les Miserables is a Broadway show, an operetta or an opera? To me, the division that’s important is between good music and bad music. If you think Les Mis is good (as I do), that’s enough for me. Call it ballet, if you want to, it won’t matter to me.

If someone hears one of my songs, likes it and hears it as pop, folk, opera or Broadway, in short, that’s fine with me. Just so long as they like it.

3. “The Eclipse” (Gayden Wren, 2017).

I usually recount the origin of this song prior to singing it, because I always worry that, if I don’t, people won’t understand the song or its governing metaphor—as I understand it, the singer himself has been eclipsed.

I did only an abbreviated version this time, though, so for the record: Back in August 2017 there was a total eclipse of the sun over most of America. Unfortunately the eclipse wasn’t total where we were, in northern Michigan; you needed to be a good bit further south. One of the best places in America to see it, as it happened, was Nashville.

The eclipse was on a Monday afternoon. The Sunday before, we attended church in Petoskey, and during the announcements the minister asked us to forgive him because he wouldn’t be around afterward for the coffee hour, because he was leaving right after the service to drive to Nashville for the eclipse. Well, the eclipse was Monday at 2, and at about 1:00 the sky clouded over and stayed that way. At about 2:15 I said to my wife, “Glad I didn’t go to Nashville.”

I didn’t think any more about it at the time, but two weeks later, as I was driving south on I-75, I found this song running through my head.

I assure you, the song has no autobiographical basis whatsoever. I’ve never been involved with a woman in Nashville, I’ve enjoyed every time I’ve been there and I look forward to revisiting the city the first chance I get.

4. “I’m Wearing the Boots” (Gayden Wren, 2016).

This one is a favorite of my nephew Maxo, probably because kids always think butt-kicking is funny. I don’t think he’ll be around for this show, but it’s dedicated to him anyway.

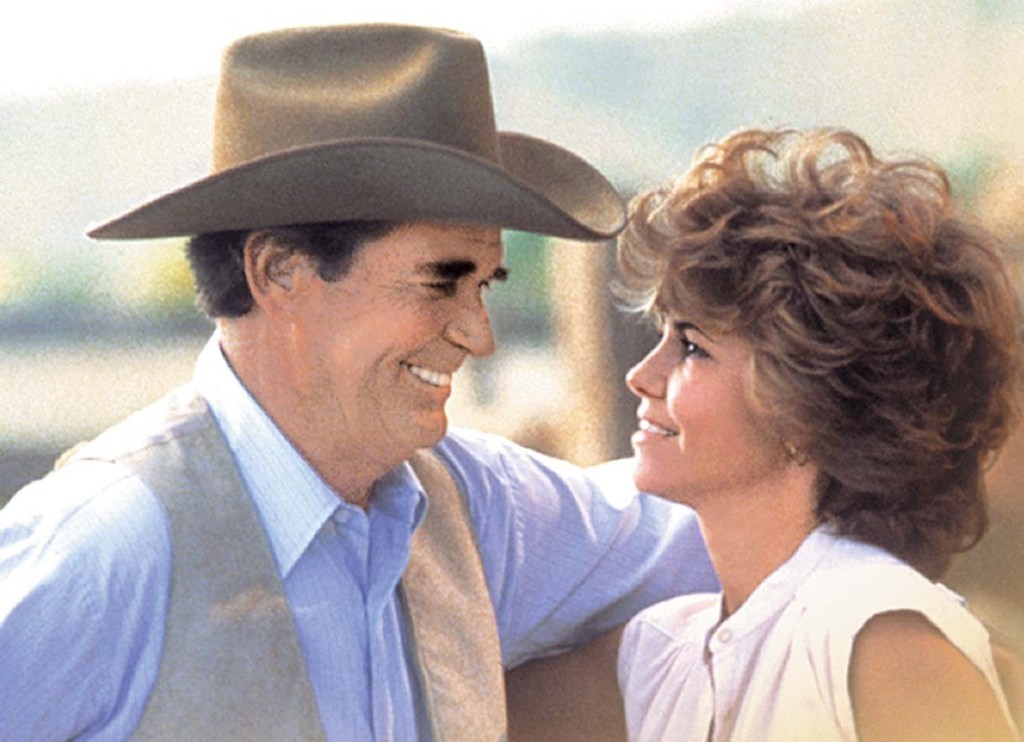

The title comes from the 1985 movie Murphy’s Romance, in which James Garner plays an aging rancher (the titular Murphy) who gets involved with a much-younger divorcee (Sally Field). At one point her no-good ex-husband (Brian Keith) shows up; after he’s said some disrespectful things about her, Murphy says to him: “And I’ll tell you something else, mister: You may be a lot younger and stronger, but you’re about to get your ass kicked from here to the state line—and I’m wearing the boots that can do it.”

It struck me as a great line the first time I saw the movie, but it wasn’t until roughly 30 years later that it struck me as a song title. I’m glad it did—it was the first song I’d written that sounded to me like a potential hit, and it’s been one of my most popular songs ever since.

5. “Michigan” (Gayden Wren, 2018).

As I said, I wrote this song in about five minutes in July 2018, while driving north on Rt. 131, coming up on Petoskey on my way to Bay View. I wasn’t at all thinking about writing a song—I was getting in for the first time that summer, and was running over my list of things to do to get settled in—but these things happen.

It’s obviously very short—the shortest song I’ve ever written, in fact. I thought at the time that it might be the chorus to a song, or maybe the first of several verses, but so far that hasn’t proven to be the case. Maybe it will in the future, but for now it’s just a very short song—albeit one that entirely expresses its core idea, so maybe it doesn’t need to be any longer. That means it’s unlikely to be released as a single, but what’s the chance of that anyway?

6. “Alanson” (Gayden Wren, 2019).

Writing music is relatively new to me, but I’ve written lyrics regularly for the past 40 years, including song parodies, rock songs, five original musicals and a variety of other incidental work. In all that time, I’ve been a very disciplined writer, sitting down and banging out the words for my various composers on a tight schedule.

Country songs aren’t that way for me. I’ve tried being disciplined, and it simply doesn’t work. The songs come to me, in various forms of completeness, when they want to, not when I want them to. I write them down as they occur, the music always right along with the lyrics; sometimes songs show up all at once, sometimes gradually over weeks or months, but it’s always on their schedule, never on mine. I’d no more promise someone a new song on a particular date than I would promise them specific weather on that date.

Which is a long way of saying that I have no idea why this song is about Alanson, or why it’s a love song. I have no particular ties to Alanson—I’ve driven through it many times, but I don’t know that I’ve ever stopped there—and I certainly was never involved with a woman from Alanson. That’s how the song came to me, though, pretty much in complete form, so that’s what it is.

7. “The Loneliest Place in the World” (Gayden Wren, 2019).

As I said, there are certain traditional subject matters associated with country. One of them is a lonely guy in a bar, wallowing in self-pity. I don’t drink, and can count on one hand the number of times I’ve been in a bar. Am I writing from personal experience? Absolutely not.

Even so, I say that “Pass me a glass of yesterday” is as country a line as anyone ever wrote.

8. “Christmas in New York” (Gayden Wren, 2018).

This is one of my most popular songs, and it began as a single line in my song book: “Rockette’s Red Glare.” I knew there was a song in there, and I even had an idea what it was going to be about—an audition for the famous Radio City dancers. Didn’t seem very country to me, though, and I couldn’t make head or tail of it anyway, so I let it sit for a couple of years.

When I next opened that drawer in my brain, the song as you hear it was waiting for me. It is at least somewhat country, as it turns out. It’s only incidentally about the Rockettes, and “Rockette’s Red Glare” is now “Rockettes’ red glare,” a throwaway line from the fifth verse, not the title after all.

And it beautifully expresses my antipathy toward cell phones, especially in any performing-arts situation. So sometimes it’s good when things don’t work out as planned.

9. “What Might Have Been” (Gayden Wren, 2015).

The idea of what might have been is, of course, a chimera. The great romance that you missed out on might have been a lifelong idyll, or it might have led to a soul-searing divorce. The dream job you almost got might have made you happy forever, or might have disillusioned you in the first year and ruined your life in the second year.

And, certainly, the idea that changing one thing would have changed everything is, 99% of the time, an illusion. The boss didn’t turn you down for a promotion because you nervously called him “Mr. Johnson” instead of “Mr. Jackson”—it was about your work. The girl in the bar probably would have said no regardless of what line you used. If Hank Williams hadn’t died on New Year’s Eve in 1952, he wouldn’t have lived to write hundreds more immortal songs—he’d just have died a few days or weeks later.

No matter. The song isn’t really about what might have been, but about the idea of what might have been. It’s a powerful idea, one that never loses its appeal, and one that we can all relate to.

10. “Three Little Words” (Gayden Wren, 2017).

My lovely wife refuses to accept that this song is about her. Trust me, it is.

The title is, of course, a reference to the classic Kalmar & Ruby song “Three Little Words” (1930); it’s also the title of the Kalmar & Ruby biopic, from 1950. In that case, of course, the three little words as “I love you.”

I hope people listening to the song will get that—I use the implied rhyme “There’s no one that’s above you”—but I think the song works even if you don’t get it.

11. “The Wrong Side of the Bed” (Gayden Wren, 2018).

This isn’t actually a funny song in the least, but it has that Johnny Cash thing of offering a depressing, ballad-like lyric in the company of a crunchy tune with a sort of rhetorical flourish that feels somehow funny. Maybe that’s why, when I hear it in my head, it’s Cash singing, not me.

Which is OK with me. I’m a writer and director at heart, not a performer, and I don’t have a conventional performer’s ego. When I hear my voice, it sounds to me like what it is: a decent enough baritone, but not in the same class as that of someone like Johnny Cash.

If I could hear all of my songs sung in his voice, I would!

12. “I’m a Liar” (Gayden Wren, 2021).

What makes this song for me is the narrative voice. I love songs with unreliable narrators, ones which, as you move further into them, turn out to be about something different than they seem to be at first glance. I’d had the words “To tell you the truth, I’m a liar” in my song book for years—who could be a more unreliable narrator than one who begins with that declaration? I knew there was a good song it, and eventually I turned out to be right.

The irony, of course, is that he turns out to be one of the more truthful of my narrators. He describes a lifelong tapestry of lies and deceit … and does it with complete honesty and, I hope, ends with some kind of sympathy from the listener.

13. “A Pod in the Basement” (Gayden Wren, 2016).

To my surprise, a significant number of people hearing this song have asked me afterward, “Did you say ‘pod?’”

Apparently they’re not familiar with the classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), in which space aliens are secretly replacing people in a small town with duplicates growing in, yes, pods in the basement. More people seem to be familiar with contemporary soap operas, in which any character may turn out to have a previously unknown twin (always, conveniently, identical and not fraternal).

If you’re not familiar with the movie, check it out—it’s cool. The 1978 remake is better acted and far more sophisticated in its filmmaking, but the original has a creepy vibe that still works today.

14. “Almost Ready” (Gayden Wren, 2021).

The entry in my song notebook read “Almost Ready to Love Me.” When the song showed up, a year or two later, it had added the word “again,” and that made all the difference. I like this one very much. And it has an unvoiced chord halfway through the chorus, which is a departure for me, in a good direction—I’ve been a lyricist since my early teens, but I’m still learning to be a composer.

15. “The Elliptical Song” (Gayden Wren, 2017).

This song violates one of the most sacred rules of storytelling: Specificity is better than generality. Don’t write “Enter a MAILMAN,” write “Enter TOM, a mailman.” Don’t say “The room was a mess,” say “Chairs were overturned, unwashed dishes and glasses were everywhere, there was broken glass by the window and an unidentifiable liquid soaking into the rug.” In writing his opera Patience, W.S. Gilbert cannily changed a single word in the following exchange and made it significantly funnier:

DUKE: Envy me? Tell me, major, are you fond of candy?

MAJOR: Yes, very.

COLONEL: We are all fond of candy.

SOLDIERS: We are!

Gilbert’s change: At the last minute he replaced the word “candy” with the word “toffee.”

Detail is powerful, generalities are flabby. That’s the rule, and yet this song goes entirely the other way. We never learn who the narrator is, to whom the song is addressed or what their backstory is. (It sound like it’s a man singing to a woman, because it’s being sung by a man here, but it would work perfectly well the other way around, without changing a word.) It’s not really a story at all, just the skeleton of one.

When this song manifested itself in my head, it was in the current form, and for a while I tried to rewrite it into a more detailed story—but it didn’t sit right with me, and I gave it up. It was several years later that I encountered the work of the great country songwriter Billy Joe Shaver and saw the powerful way in which he strips his stories down to the nub in such songs as “Because You Asked Me To” (1973) and “Black Rose” (1973). It’s not the normal way, but there’s a power in the absence of detail—it lets the listener fill in the details for him/herself.

Read my blog essay on Billy Joe Shaver, especially if you know his work. It’s all about the power of the absence of detail.

16. “That’s Just Some Guy” (Gayden Wren, 2016).

Another of my unreliable-narrator numbers, in the voice of some guy who protests way too much.

It never ceases to amaze me what stupid things people do in front of cameras, live microphones and the like. There was a time when these things were the result of technological change, with people caught unawares by cameras, microphones and such, but today we live in a surveillance age, an age in which anything that can be seen or heard can be posted on the internet. How is it that people—movie stars, pro athletes, police officers, politicians—keep doing such prodigiously stupid things?

Well, at least it’s a reliable source for public humor. That’s something.

17. “Footsteps” (Gayden Wren, 2019).

My old friend Izzy from Massapequa thinks this song is about George W. Bush, and dislikes it on that basis. It’s arguable that the first verse is about W, but if I had to pick a model for it (which I don’t, and the following answer has only just occurred to me for the first time), I’d go with Ron Reagan Jr.; I think W generally votes the way his father did.

For the second verse, almost any billionaire’s child would do. The third verse, maybe Julian Lennon. The fourth verse … well, that’s me.

18. “Things That We Don’t Say” (Gayden Wren, 2018).

A longtime friend of mine has said, and I agree, that nobody really understands a marriage except the people that are in it. Even if you’re close to both people, and hear both sides in detail, you still don’t really know; even if you’re the child of that marriage, you still don’t really know. You have to be there, and there’s only two people that are.

My outside analysis of the marriage that this song is about (and it is about a real marriage) is that the two people grew apart, in the classic sense. One of them matured and took on responsibility and worry; the other remained youthful and exuberant, at least in spirit, despite the passing years. By the time I got to know them, they were living essentially separate lives in the same house. I think they both regretted it, but felt that it was too late to change anything.

I’m pretty sure that this won’t be happening in my marriage; no signs of it yet, in any event, 21 years in.

19. “Aruba” (Gayden Wren, 2021).

I’ve never actually been in Aruba, and in general am not a vacation-resort kind of guy. I don’t care for beaches, except as places for long walks. I spend my vacations in northern Michigan, in a cottage my family has had since 1895 (it’s referred to in the final verse of the song). In this song it’s used as an emblem of the ineffably desirable elsewhere, which everybody has in one form or another.

Call it “Shangri-La,” if you will, or “over the rainbow”—it’s that place where everything is easy, everything makes sense, everything is good. I don’t know what yours is called, but everybody has one.

20. “Making the Same Mistakes All Over Again” (Gayden Wren, 2017).

This was one of the easiest songs I’ve ever written. The song came to me in two verses, almost exactly the same as the current first two. I thought to myself that it needed one more, something of an overview; and, an hour or so later (during which time I was doing other things), I looked back in on it and it had three verses.

It’s nice when that happens. Doesn’t always.

(Incidentally, I seem to be different from most songwriters, who typically say that the first verse they write is the last verse of the song, then the first, and then they fill in the blanks. Most of the time I write the first verse first and the second verse second; it’s not unusual for the last verse to come some time after the rest of the song, but it’s almost always the last one I write.)

21. “Jimmy Buffett” (Gayden Wren, 2018).

I’m indebted to my old friend Sally Denmead and her husband, Jonah Winter (also by now an old friend), for the existence of this very popular song.

A few years ago my lovely wife and I were chatting with them at their house in Pittsburgh, and the conversation turned to strange, unaccountable events. I held the floor for a considerable period recounting my 2010, a year during which—besides the events recounted in this song—I was also misdiagnosed with a fatal disease and, through a bizarre set of circumstances, was widely believed to have murdered my mother.

When I told the story of me and Jimmy Buffett, Jonah said, “There has to be a song in that.” Sally chimed in to second the notion. I wasn’t convinced—it seemed odd but not in any way resonant, nothing with enough scope to make up a decent song. I laughed it off.

But the next day I was driving us home to New York on I-80, and my lovely wife dozed off as we passed through the Delaware Water Gap. I soon noticed bits and pieces of the song as it eventually emerged bouncing around in my head. For want of anything else to do as we headed through southwestern New Jersey (the area where Sally grew up, coincidentally), I thought it over and the song came together in my head. I sang it to Sara as we unloaded our luggage, and there it was.

Since then it’s scored a hit whenever and wherever I’ve done it, and I owe a percentage of the applause to Jonah Winter and Sally Denmead. Thanks, both of you!

22. “Bridges Are for Burning” (Gayden Wren, 2019).

This is another one that came together in a hurry—the best ones usually do—after marinating for a while in my song notebook (and, thus, in the back of my mind).

It’s loosely autobiographical, in that it expresses my attitude toward risk-taking (at least of the artistic sort) and my parents’ skepticism about same. I should emphasize, though, that—while my parents viewed my theatrical career with skepticism—they were both supportive of it and of me. Both wished I were devoting my life to something more likely to be lucrative, but they could tell what I wanted and they wanted it for me.

(Had they lived to see my late-blooming musical career, I think my father would have been even more perturbed. My mother was a big fan of country music, though, and might have warmed to the idea. Sadly, we’ll never know.)

In any event, my mantra as an artist and as a person might be, “After all, until you try, you never really know.” Because, after all, you don’t.

23. “Stanley’s in His Garden” (Gayden Wren, 2018).

I think it was in 2016 that I first was subjected to one of Stan Bergman’s lengthy discussions about his garden … and found myself unaccountably fascinated. It was the middle of the first Trump campaign, the world seemed to be going to hell and both Stan and I were really upset about this. But what he really wanted to talk about was his garden. He showed me his map of the current garden, and the sketched-out diagrams for what he was planning to do next year, and I found myself as caught up in it as he was.

I don’t really care about gardening—didn’t then, don’t now. I think what caught me up was the implicit optimism of the whole thing. I wrote the words “Stanley’s in his garden” in my song notebook. Then, one day in 2018, I flipped through the book, saw that note, checked the corresponding spot in my brain, and there was this song, virtually as you hear it today. Without my giving it any attention at all, it had sprung up, blossomed and produced something beautiful out of nothing.

As long as that still goes on—in our soil and/or in our minds—there’s still room for hope.