Island Trees Public Library, April 12, 2025

“Streets of Bakersfield” (Homer Joy, 1972).

This song was the last of Buck Owens’ 20 No. 1 hits, and an absolute fluke. In 1988 Owens and Merle Haggard were scheduled to appear at the Country Music Association Awards and sing a duet. At the last moment Haggard couldn’t make it, and Dwight Yoakam was roped in to sing with Owens; asked for a song that would evoke the Bakersfield Sound, Owens suggested Homer Joy’s song from 15 years earlier—“Streets of Bakersfield,” which had never even been released as a single. It went over extremely well, and a few weeks later Owens and Yoakam went into a studio to record it … and then watched in amazement as it rose to No. 1 on the charts.

The song was apparently written out of frustration, as Joy kept hanging around Owens’ studio in Bakersfield, waiting for a recording session he thought he’d been promised, only to be put off by the studio manager, returning day after day to no avail. The “you” is presumably the studio manager. When a song is very specific, however, those not aware of the original context hear the song in a broader context: “Let It Be,” for example, is apparently about Paul McCartney’s mother, who was named Mary. That’s certainly the case here, because a generation of Bakersfield musicians adopted it as an anthem.

Actually, Owens’ 1973 recording wasn’t the original recording, though it was the first to receive a wide release. Joy actually made the first recording, on a single put out by Buck Owens Enterprises, in 1972; Owens recorded it the following year, but it would be another 15 years before the Owens/Yoakam version became a hit.

Here’s Joy’s own recording, which I actually like better than either Owens recording—it’s simpler and cleaner. The 1973 Owens recording is also strong; I’m not partial to the 1988 Owens/Yoakam recording, which is the version everybody knows—it’s a good recording, but to my ears it’s overproduced.

“Philadelphia Lawyer” (Woody Guthrie, 1937).

Guthrie used a folk tune called “The Jealous Lover” as the basis for “Philadelphia Lawyer” (originally called “Reno Blues”), which is based on an actual 1937 case in Reno. Listening to the original (say, in this 1926 recording by Vernon Dalhart) doesn’t kindle any regret that the Guthrie version is far better known. Here’s Rose Maddox and her brothers doing “Philadelphia Lawyer” and, for extra Bakersfield Sound cred, Bonnie Owens in a live performance of the same song. And, why not, Willie Nelson as a bonus.

“Dim Lights, Thick Smoke and Loud, Loud Music” (Joe Maphis, 1952).

It’s natural that there are a lot of country songs about honky-tonks, since most professional country musicians make their livings playing in clubs, but it’s striking that so many of those songs—including this one, the next song and Hank Thompson’s enduring “The Wild Side of Life”—take a negative view of the whole thing, primarily on moral grounds. They also tend to focus on the women there, seeing them variously as predators and victims. Like I say, strange.

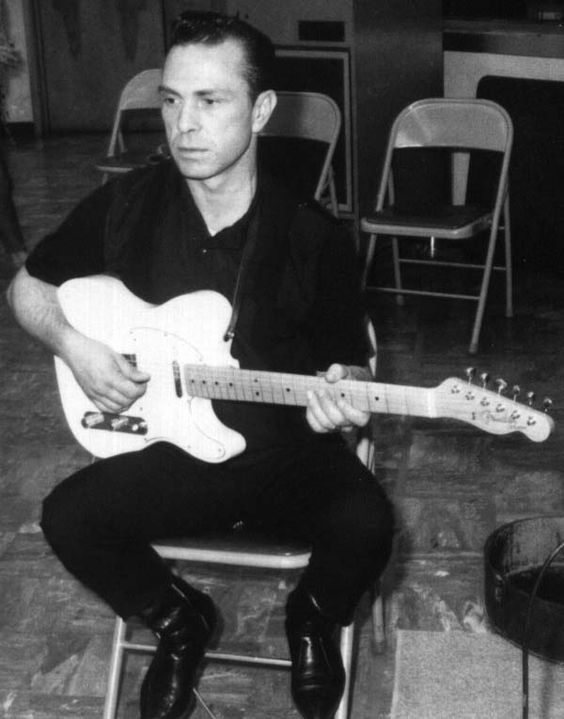

Maphis was born in 1921 in Virginia, and grew up in Maryland. He and his wife, Rose Lee Maphis, performed in several parts of the country before settling in Bakersfield in the 1950s. She was primarily the singer of the duo; Joe sang and wrote songs, but was best known as a flamboyant guitar player.

“Dim Lights” was a modest hit at the time, but has become a honky-tonk classics. Here’s the Maphises’ version of “Dim Lights, Thick Smoke and Loud, Loud Music,” from 1953. It was actually the second recording of the song, following the original by Flatt & Scruggs in 1952. For a later version, here’s Dwight Yoakam in 2012.

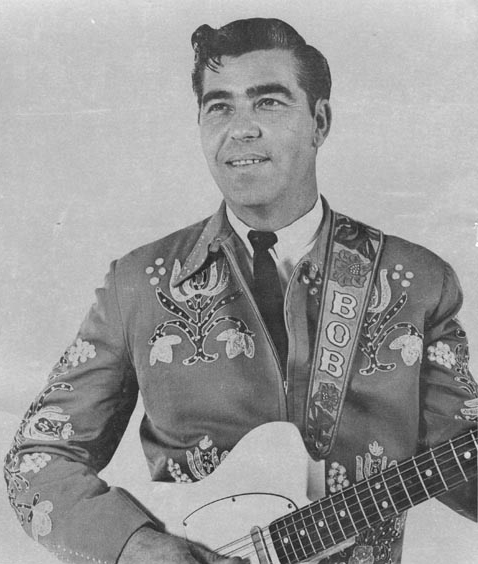

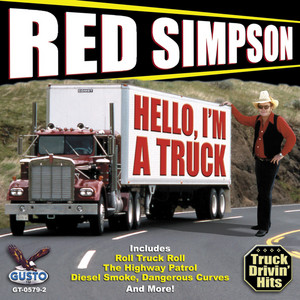

“Close Up the Honky-Tonks” (Red Simpson, 1964).

If you’ve just seen my show From Bakersfield with Love, it’s statistically likely that you heard me get the lyrics wrong on this song. The title phrase occurs four times in the song … and I get it wrong, singing “close all the honky-tonks,” about one out of every four times. What can I say? I know what the lyrics are—it’s some kind of mental block. Hopefully, as I do the show more and more, my lapses will become less frequent, but I doubt they’ll ever disappear entirely.

Here’s Buck Owens’ terrific recording of Simpson’s song, from 1964. And, for those who feel that all these my-girl’s-in-a-honky-tonk songs are sexist, here’s a fine recording by the great Amber Digby from 2004.

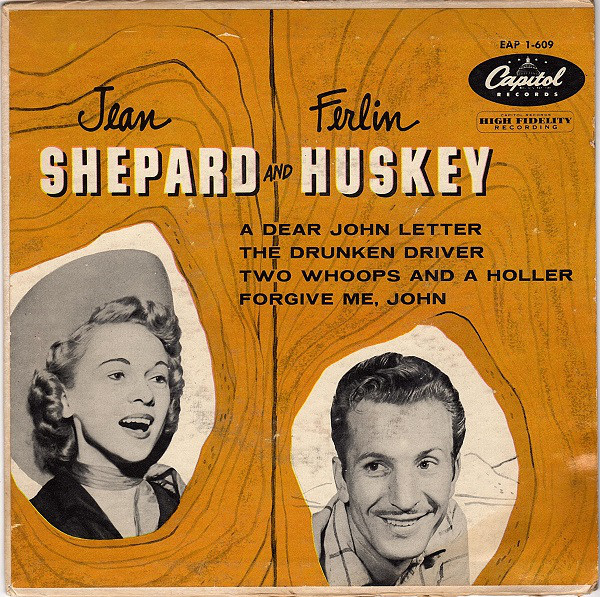

“A Dear John Letter” (Billy Barton, 1953).

Truth to tell, I don’t love this song—it’s included in this show because of its historic significance. Mostly I don’t like it because I don’t like recitations in songs. I come to a song for the singing, not the talking. (I make some allowances for comic recitations, but this isn’t one of those.)

Nonetheless, it was a huge hit, and has been covered by a Who’s Who of country legends, including Loretta Lynn (and Ernest Tubb), Skeeter Davis (and Bobby Bare) and many more. Here’s the somewhat lugubrious first recording, with Bonnie Owens and Fuzzy Owen, and the hit with Jean Shepard and Ferlin Husky.

And here’s the answer song, “Forgive Me, John,” sung by Shepard and Husky, and Stan Freberg’s parody version, “A Dear John and Marsha Letter.”

“A Satisfied Mind” (Red Hays and Jack Rhodes, 1954).

The original recording of this song was by its co-author, Joe “Red” Hays, a little-known singer and fiddler who today is known only for writing this song. Nonetheless, his recording is an excellent one.

Jean Shepard’s recording, the following year, “made” the song, hitting No. 4 on the country charts, followed immediately by Porter Wagoner’s recording, which hit No. 1 and made a star out of Wagoner.

An interesting feature of this recording that has carried over into most of the cover versions is the lack of any connective tissue between verses one and two and verses three and four—except for an instrumental break between two and three, each verse follows immediately after its predecessor.

Almost all citations of this song spell the co-author’s name as “Hayes,” but the label of the original single and the family’s spelling of the name make clear that it’s “Hays.”

“Second Fiddle to an Old Guitar” (Betty Amos, 1964).

[Included only in shows with Texas Sally guesting]

It’s beyond me why this delightful song hasn’t won more long-run popularity. It was a No. 5 country hit for Jean Shepard in 1964, and was quickly covered by Lulu Belle and Scotty and by Jean Gray that same year. It even lent its title (almost) to a 1965 “countrysploitation” movie, Second Fiddle to a Steel Guitar.

Since then, however, it’s been recorded exactly once: by a Czech country band named Krajanci in 1979.

No idea why. What a great song! (Special bonus: Here’s Shepard performing the song live on The Grand Ole Opry. The very capable guitarist is Walter Haynes.)

“Another Day, Another Dollar” (Wynn Stewart, 1962).

If this song rings a faint bell, it may be because it was used in a nationally aired Volkswagen commercial in 2011.

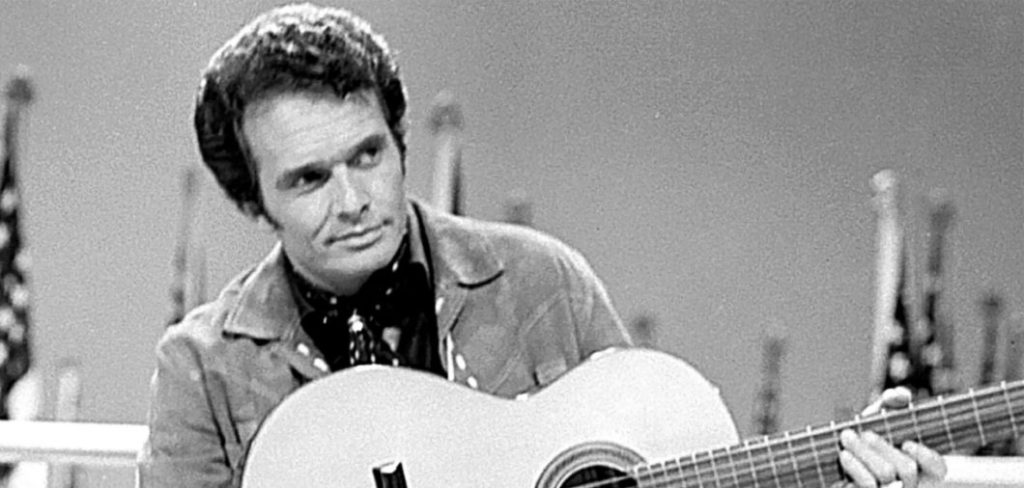

Stewart’s recording is one of his most Bakersfield Sound songs. The guitarist is the great Roy Nichols, who later spent a couple of decades as one of Merle Haggard’s Strangers; Haggard and Nichols met in 1960 as members of Stewart’s band (Haggard was on bass). Haggard isn’t on this recording, though—Bobby Austin is the bassist. Nichols stayed with Stewart for five years, but Haggard moved on in less than a year.

Nichols is one of the bedrock musicians in the Bakersfield Sound, influencing the work of generations of guitarists, including Buck Owens, Don Rich and Merle Haggard. He played for a year and a half with the Maddox Brothers and Rose (because the 16-year-old Nichols was underage, Fred Maddox became his legal guardian), then in Lefty Frizzell’s band, and from 1955 to 1960 he played on Herb Henson’s influential Bakersfield television show Cousin Herb’s Trading Post, during which time he also toured with Johnny Cash.

That said, Nichols’ guitar work on this particular song isn’t especially noteworthy—it’s drummer Helen “Peaches” Price (a rare female band member) who’s most impressive.

Here’s a much more elaborate recording by Porter Wagoner, from 1965. It’s not very Bakersfield, but it’s good.

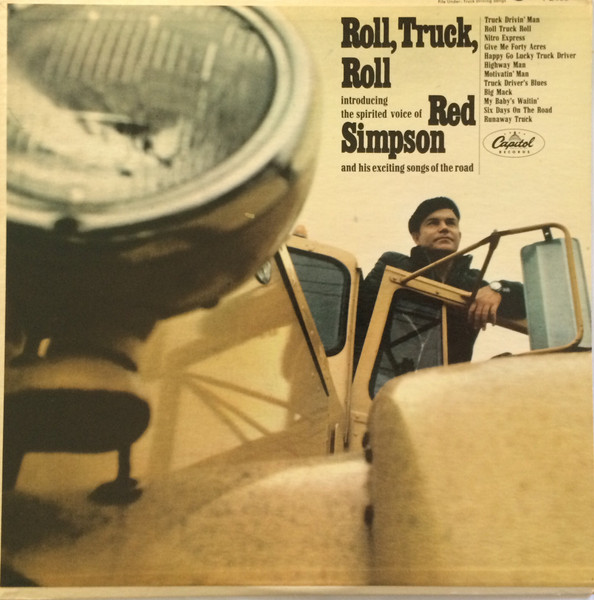

“Highway Patrol” (Red Simpson, Dennis Payne and Ray Rush, 1966).

When you think about highway patrols, you think about speeders; when you think about speeders, you think about trucks; when you think about trucks (if you’re into country music, anyway) you think about Red Simpson.

There are a number of recordings of this song, but the two that really matter are the original one by Red Simpson and the 1993 one by Junior Brown. (Brown is a confirmed Simpson fan who, a couple of years after making this recording, recorded two duets with Simpson—predictably, both truck-related songs: “Semi-Crazy” and “Nitro Express,” the latter a cover of a Simpson song from 1966.)

Both recordings are terrific. I heard the Brown one first, and I’ve heard him perform the song live, so I have a sentimental attachment there … but, all told, I think Simpson’s is a tad better. He sings with such panache.

“Truck-Driving Man” (Terry Fell, 1954).

[Deleted, because the show was running long, but why not include it here?]

The thing that strikes me about this song is that it appears to have a meta touch to it: The song is about a truck driver who pulls off at a hamburger joint, goes inside and hears the jukebox playing … the song we’re actually hearing.

Truck-driving songs have long been a staple of country music, and no wonder—interstate truckers, on the road all day or night, sometimes for days on end, are a natural audience for country radio. There are examples of this subgenre going back to the 1930s and enduring to the present day (for example, Sturgill “No Relation” Simpson’s 2014 cover of the Charlie Monroe/Bill Napier classic “Long White Line”), but there was a particular boom in the mid-1960s, and Red Simpson was lucky enough to ride the wave.

Four versions for you here: The Terry Fell original, on RCA Records in 1954, opens with a kickass harmonica solo, and the whole thing has a fast, driving beat that is hard to resist. Buck Owens played and provided backup vocals on Fell’s version, and a decade later returned to it for his own version, which has more of a drifting, road-hypnosis feel. (He omits the fourth verse, for no obvious reason.) Red Simpson’s 1966 recording is midway between the previous two in tempo, and features an aggressive Bakersfield arrangement with a honky-tonk piano and a strong guitar solo; he also brings back the final verse. Finally, Leon Russell’s 1973 live version is super-fast (the audience struggles to keep up) and features bluegrass virtuosity from the band—not for everybody’s taste, but its energy is infectious.

“Act Naturally” (Johnny Russell, 1963).

The Beatles famously had a standing order with Capitol Records that any new Buck Owens records be shipped directly to them in England.

That makes sense, because Owens was the most rock-oriented of the major Bakersfield Sound artists. In fact, his first record ever was a rockabilly record, a single called “Hot Dog,” from 1956. Because he was committed to a career in country, however, and knew that many country fans disliked rockabilly stars on principle, he released it under a pseudonym, Corky Jones.

Here’s “Act Naturally” as rendered by a) Buck Owens in 1963; b) the Beatles in 1965; and c) songwriter Johnny Russell in 1971. And, why not, the Buck-and-Ringo video version from 1989? Or Loretta Lynn in 1963? Kitty Wells in 1964? Well, whatever—lifelong Beatles fan though I am, Owens is still my favorite on this song, though Lynn and the Beatles are both excellent.

Oh, and here’s Corky on “Hot Dog!”

“Hello, Trouble” (Orville Couch and Eddie McDuff, 1962).

I see why this song appealed to Owens, who must have loved its extreme syncopation. It’s short, funny and insanely catchy.

To me the most striking thing about it is the way the final note of each verse is a high C, rather than the expected middle C. It’s right in the chord, of course, but it feels strange and, given that the rhythm is already unpredictable, it makes the whole song hang in uncertainty for just a moment—to be perfectly resolved, of course.

Here’s Couch’s recording, which is a nice recording, but lacks the energy of Owens’ version. Very few bands had the dynamism of the Buckaroos, and that comes through in “Hello, Trouble.”

“I’ve Got You on My Mind Again” (Buck Owens, 1968).

To me this is the discovery of the year, a song I’d generally liked in the past, but really got into only when I started considering it for this show and, in particular, once I started working on it in my practice sessions.

What I particularly like about my arrangement is my use of band cutouts, where the piano drops out and the singing carries the song alone—perhaps because I am, by general agreement, a better singer than I am a piano player. This is one of Owens’ favorite devices (see the previous “Hello, Trouble,” for a great example), but he doesn’t use it here; that’s my idea.

It puzzles me that this gorgeous song, which was a No. 5 country hit in 1968, has been so little covered in the following decades. In more than 50 years, there have been only two major covers, by the great Kitty Wells in 1969 and by Owens protegee Susan Raye in 1972. These are both good recordings—though neither matches the original, in my opinion—but still it’s only two covers. There are far worse songs that get hundreds of covers.

If I had to guess, I’d say that it’s because the lush arrangement—at the very least, it’s a Nashville Sound style, and arguably it’s outright pop—prejudiced country fans against it. If what you like is Hank Williams or Ernest Tubb (or, for that matter, Merle Haggard), this may not be your cup of tea. Personally, I like all three of those guys and also this song; you can call it “country,” you can call it “Nashville Sound,” you can call it “pop”—I call it “great.”

Here’s Kitty Wells in a close take on Owens’ original arrangement, and Susan Raye in a very enjoyable honky-tonk take. I particularly like Raye’s version, but not quite as much as I like the Buck Owens original.

“Let the World Keep On a-Turning” (Buck Owens, 1968).

This is an interesting song for its structural key changes. Most country songs are in a single key, but it’s not unusual to find a song such as Loretta Lynn’s “I Want You Out of My Head (and Back in My Bed)” which modulates (almost always upward in key) for an added kick on the final verse or chorus.

“Let the World Keep On a-Turning” is highly unusual, though, in that its chorus is in G and its verse in C, so that the key change is a structural feature, not a choice in the arrangement. There are a total of five key changes in a single two-minute song—and instead of an artful transition each time, it’s a smash break from C into G each time. Owens is a much more inventive songwriter than he’s given credit for.

Here are two versions, one the Owens original and the other a 1969 cover by Ernest Tubb and Loretta Lynn, two of my all-time-favorite country singers. The effect of the song is quite different when it’s sung by a mixed couple, as opposed to a single soloist as in the Owens version. I love E.T. and L.L., but the Owens version has an energy that, to me, sweeps everything before it.

“No. 1 Heel” (Buck Owens and Bonnie Owens, 1965).

My guess would be that Bonnie wrote the lyrics and Buck had a lot to do with the music, which has all of Owens’ signature traits, notably strong syncopation (“I’m the (beat) top of the list, it’s plain to see”) and band cutouts (on the “Oh, I’m the,” for example). And Owens sings it with brio.

Another reason for thinking that the lyrics were primarily by Bonnie are that it’s been covered by only two other artists: Owens herself later in 1965 and Kenni Huskey in 1972. Both are women, and both sing the song as “You’re the number-one heel in the country” and “I’m the number-one fool.” Which makes more sense, but the fact that Owens’ original 1965 version is sung from the male point of view gives it a certain freshness. Country certainly has no shortage of female artists singing songs about still loving men who don’t deserve them.

Incidentally, Kenni Huskey is no relation to Ferlin Husky. She was a Buckaroo, singing and occasionally recording duets with Buck Owens, from 1971 to 1976. She signed on with Owens, who was also her manager, when she was only 15, and in 2006 recorded an album called A Tribute to My Second Dad … Buck Owens.

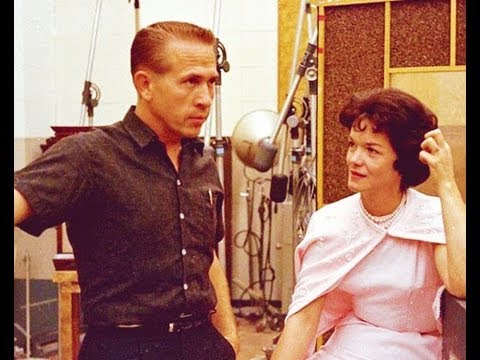

“Just Between the Two of Us” (Liz Anderson, 1964).

Originally recorded as a single on Tally Records in 1964, this became the title song of the first Bonnie-and-Merle duet album on Capitol Records in 1966, after Capitol bought Haggard’s masters from Tally in 1965.

It’s worth noting that the album was billed as “Bonnie Owens and Merle Haggard,” and that’s not an exercise in chivalry on his part. Owens, who the previous year had won the Academy of Country Music’s award for Female Vocalist of the Year, was the bigger of the two stars at the time. Haggard himself credited Owens with boosting his career by touting him to Capitol and helping convince them to sign him.

Here’s their version of the duet, which is outstanding. The Ernest Tubb/Loretta Lynn version from 1965 is good, but lacks the sexiness of Owens and Haggard. Most of the time I perform this song, I do it as a solo, not a duet—following in the footsteps of Charlie Louvin’s version, which came out in 1964 as the first cover of the song, and the first solo version; his twangy take, with a keening steel, is quite nice in its own right. And, just to round things out, here’s the 1966 version by Lyn Anderson, who wrote the song in the first place; her take is all-out Nashville Sound, with a crooning chorus, and plays it (for some reason) as seductive.

“If You Can’t Bite, Don’t Growl” (Tommy Collins, 1965).

This song was Collins’ comeback hit after his sabbatical to serve in the ministry. I can’t capture Collins’ high-energy performance of the song, but I have fun trying.

The song interests me for its humorous depiction of a familiar phenomenon, a man who is sexually aggressive as long as women don’t follow suit, but backs down when the fantasy turns real. We all know Don Juan types who are all talk, no follow-through, and it’s clever of Collins to have used this as the basis for a song.

Oh, and if you want to know what a “wampus kitty” is, well, the wampus cat is a folkloric creature, a six-legged feline sometimes depicted as terrifying and other times as mischievous. In this case, the wife is probably somewhere in between. See the picture below, and here’s a Wikipedia summary.

“It Hurts to Know the Feeling’s Gone” (Doodles Bowen and Warren Robb, 1976).

Mize is an artist who today is largely remembered for one song, “Who Will Buy the Wine” (1956). “It Hurts to Know the Feeling’s Gone” is so obscure as to be one of only two songs in this show not to be found on SecondHandSongs.com, an otherwise invaluable research source. (The other one is “If You Can’t Bite, Don’t Growl.”) Nonetheless, it’s the best of his songs that I’ve heard, and as soon as I came across it on YouTube, I knew I wanted it in From Bakersfield with Love.

The style is obviously heavily influenced by Kris Kristofferson, but to me that’s nothing but a recommendation—I love Kristofferson and, if I could write songs like him, I would.

What I like about this one, I think, is the acute (and scathing) portrait it paints of the narrator. This could be a simple “my gal done left me” song, driven by anger, irony or grief, but instead the defining characteristic of this guy is his passivity. There’s almost nothing in this song that comes from him—she’s the driver of it, and ultimately all he does is lie there and watch her leave.

We know from the lyrics that he’s frequently stoned—often enough that she’s chosen to tell him she’s leaving first thing in the morning, waking him up for that purpose, because presumably he’ll be stoned as soon as he gets up. He’s cheated on her, but even he doesn’t know why he did. And as she methodically goes about leaving—opening the curtains, putting on the coffee, waking him, telling him she’s leaving, getting dressed (in “unfamiliar clothes,” a very nice touch), taking off his ring and walking out the door—all we hear of him is the fact that he’s begging her not to leave him. We hear of no response, and it seems unlikely that there is one, because her mind is made up.

It’s such a great lyric, with a fine tune sung beautifully by Mize. Glad I can help it be at least a little better known.

Here’s Mize singing the song and, as a bonus, “Who Will Buy the Wine.” The latter is a honky-tonk song that’s also a “my gal done left me” song, but way more cynical and spiteful than “It Hurts to Know the Feeling’s Gone.” It’s been covered by some really major country stars, including Ernest Tubb and Merle Haggard. (And, yes, it has a lot in common with “Dim Lights, Thick Smoke and Loud, Loud Music,” which was released only three years earlier. The resemblance may not be a coincidence, since Mize and Joe Maphis traveled in the same circles and performed together many times.)

“Mama’s Hungry Eyes” (Merle Haggard, 1969).

This song is often described as autobiographical, and I think subtly dismissed as such—as if, having lived the song, it wasn’t that hard for Haggard to actually write it.

I don’t think that’s a fair verdict, but in any case it’s clearly not autobiographical, because Haggard didn’t grow up in a labor camp and didn’t watch his father show “a little loss of courage as [his] age began to show.” The narrator of this song isn’t Haggard, so if you think less of it for being autobiographical, well, think more of it.

Like many great songwriters, Haggard had the gift of being a great listener. This song isn’t his story, but it’s the story of someone he knows—maybe one particular person, but just as likely any number of nonspecific people. He grew up with people like these, he heard them and it stayed with him.

That’s what great songwriters do, and Haggard was one of the greatest. Here’s his powerful original version, and interesting, deeply moving covers by Emmylou Harris and (of all people) Kinky Friedman.

“Mama Tried” (Merle Haggard, 1968).

This seems like a prison song, which is a country subgenre that goes back to even before the Bristol Sessions—think Vernon Dalhart’s “The Prisoner’s Song” (1924), the first country song ever to sell 1 million copies—but it’s actually something else: It’s a beloved-mama song, which has been a staple of country since forever.

The inspiration for the song came from, of all things, a court transcript—or, more accurately, the remarks by a defense attorney and by a judge, the attorney being Ralph McKnight, defending Haggard against charges of armed robbery, and the judge being Norman F. Main, who would decide whether he would go to prison.

After Haggard had been convicted by a jury (inevitably, since the evidence was overwhelming), McKnight pleaded for leniency out of compassion—not for Haggard, a hardened repeat offender, but for his poor old mother, Flossie Haggard. “Your honor,” he said, “this mother has tried very hard.”

Judge Main wasn’t buying it. His verdict began, “If he had tried half as hard as his mother did … “ and ended with “three to five years.”

Haggard obviously had a lot on his mind that day, but clearly their words stuck in his head—and, 11 years later, became the title of one of his greatest songs.

It was also a favorite song of the Grateful Dead, who played it at Woodstock. Here’s Haggard’s classic version. And here’s the Dead with a jaunty cover.

“All My Friends Are Gonna be Strangers” (Liz Anderson, 1964).

The question of what makes a hit record is an eternal one, because it’s eternally unanswerable. Being sung by a great singer, as this one was, is definitely a big part of it; so is a catchy tune, a lyric that most listeners can relate to and so forth … but there are plenty of records that have all of that, and nonetheless weren’t hits.

I think a single line can make a big difference, though, if it’s clever and unexpected. Most of this song is fairly pedestrian, as country lyrics go, but then it kicks into the chorus and the memorable line, “the only thing I can count on now is my fingers.” That comes out of nowhere, and catches the ear.

Haggard knows it, too. One of his hallmarks was singing in short phrases, breaking up lines in unexpected places, which ensured that he’d have all the breath he needed when it counted. Listen to the chorus here, for example, and you’ll find that his version goes “from now on,” “all my friends” “are gonna be strangers.” “I’m all through” “ever trusting anyone.” But when he hits the big line, he powers through it smoothly and without a break: “The only thing I can count on now is my fingers.” For the final line, he returns to short phrases: “I was a fool” “believing in you” “and now you are gone.”

This is still very early in Haggard’s career, but he’s already not just a man with a beautiful voice, but also an outstanding singer. It would have been easy enough to sing this key line as “The only thing” “I can count on now” “is my fingers,” but he knows better.

Check out Haggard’s original recording to see what I mean. And to prove that this was Haggard’s choice, here’s Liz Anderson herself singing the song in 1966, and not breaking lines at all the same way. For a nightmarish counterexample, here’s the great Don Gibson, a Country Music Hall of Fame songwriter in his own right, butchering the song with the aid of Spanish guitars, the Jordanaires and a tempo so slow that he seems to be on the brink of losing interest and not finishing it.

“Today I Started Loving You Again” (Merle Haggard and Bonnie Owens, 1968).

To me this classic country song—not a hit at the time, but since then recorded brilliantly by scores of country singers—is actually three songs in one, because the emotion shifts discernibly from verse to verse.

The first verse is a familiar country wallow, the guy who’s lost his gal and, with her, all sense of meaning to his life. He’s tried to get past it, to move on, but it can’t be done.

In the second verse his anger kindles—not at his lost love, but at himself: “What a fool I was … “ “I should have known … “ He sees how pointless his misery is, but even that realization won’t snap him out of it, so he blames himself for being so weak and vulnerable.

The third verse recapitulates the first, but with a sense of perspective and a bittersweet humor—a trace of a laugh at his own folly, and hence possibly some hope of emerging intact. In the first line of the third verse, notice Haggard’s tiny little catch before the last word: “And today I started loving you. Again.” It’s a subtle touch that makes an already-great song just a little greater.

The best musician I’ve ever known once told me (and a bunch of other people) that, if you have to sing the same line a second or third time, you should sing it a little differently each time. Merle Haggard would seem to agree.

Here’s Haggard’s hard-to-top original, along with two great female versions: Connie Smith brings her world-class voice to a bluesy version with a tinge of a swing to it, while Loretta Lynn makes a bold choice, turning things upside down: She and producer Owen Bradley suggest a different, sunnier take on the story: This is about a woman who’s strayed from her love, but despite herself has found her way not only right back where she’s really always been, but also right back where she belongs.

I love a lot of country songs, but there aren’t many that I love more than this one.

“Okie from Muskogee” (Merle Haggard and Roy Edward Burris, 1969).

I’ve had people come up after shows to argue with my assertion that this song is obviously tongue-in-cheek, and I just don’t get it. Setting aside the obvious comparisons between the narrator of the song and Haggard himself, and ignoring the testimony of Haggard’s bosom buddy Willie Nelson, the song itself makes the case. Even if you don’t know a thing about Haggard, a line like “Leather boots are still in style for manly footwear” is a dead giveaway: Tough guys (and Haggard was an actual tough guy, not a rhinestone cowboy) don’t use phrases like “manly footwear” seriously.

Here’s Haggard’s iconic version, and here’s Kinky Friedman’s equally iconic (albeit in a different way) “Asshole from El Paso.” And, for scholarly reference, here’s the original, much rawer version of Friedman’s song, sung by Chinga Chavin, who co-wrote it; if scabrous humor offends you, you might want to skip this one.

“If We Make It Through December” (Merle Haggard, 1973).

A neat detail of this song is the twist it takes with the beginning of the middle eight (“got laid off down at the factory … “). In country music, “we” is idiomatically understood to refer to the singer and his/her significant other, and for the first third of the song that seems to be the case. (And, indeed, the song was inspired by Roy Nichols talking about his wife.)

A third of the way through the song, however, the rug is pulled from beneath the listener’s feet, as we learn that “we” is a father and his young daughter; her mother isn’t mentioned, and there’s a strong sense that this is a song about a single father.

When Haggard repeats the first eight lines as the final eight lines, therefore, they have a different feeling than they did the first time we heard them. It’s a very craftsmanlike bit of work from one of America’s greatest songwriters.

Here’s Haggard’s definitive version, and also a nifty 1993 version from Alan Jackson, who’s perhaps the most overtly Haggardian singer working today. His take is very much along Haggard’s own lines, but with a bit more swing and a nice banjo accompaniment by Mark Casstevens.

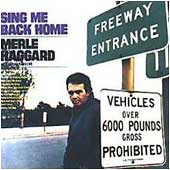

“Sing Me Back Home” (Merle Haggard, 1968).

This may be my favorite Haggard song, for the way in which it takes a familiar aspect of music—the way hearing a song can transport you back to when and where you first heard it—and gives it a new, powerful impact by associating it with a prisoner on Death Row. The song is overtly a sad song, as the prisoner’s godly childhood is contrasted with where he’s ended up, but in the fact that the dying man finds comfort in the music there’s a sense of grace as well.

Unanswerable question: Is the “guitar-playing friend” the prisoner asks for Haggard himself? I don’t know, but I like to think so.

Here’s Haggard’s classic recording, and here’s a sensitive version (for which he more or less apologizes before singing) by Buck Owens. (This is a live recording, from a show in London, and Owens’ band for this performance isn’t especially well suited to the material, but his performance is a strong one and the London audience seems to appreciate it.)

And a strange, hesitant but heartfelt performance (on the piano!) by the Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards.