North Merrick Public Library, February 15, 2026

“Just the Other Side of Nowhere” (1970).

This song is from Kristofferson’s first album, and is clearly autobiographical in its portrait of a young man from a small town who has come to the big city hoping to prove himself there, but instead feels that he’s losing himself in the soul-less city and is on the brink of giving up and heading home. Make the small town Brownsville, Texas, and the big city Nashville, and the parallels are clear … even if the song never mentions “music” or “songwriting.”

As is usually the case, though, even Kristofferson’s bleakest songs are enlivened by clever wordplay. Among the many examples in this lyrics are the unexpected pairing of “nowhere” and “know where,” the parallelism of “Sick of spending Sundays wishing they was Mondays” and the clever internal rhyming of “tell them that the pride of just the other side of nowhere’s going home.”

The official original recording is this blandly cheery one by George Hamilton IV, but the classic version is Kristofferson’s own recording, from Kristofferson. For added thrills, here’s a swinging Dean Martin recording from 1972 (kitschy, but actually not bad) and one by John Prine and Mac Wiseman from 2007. (Prine was a Kristofferson protégé.)

Can’t decide whether you like Kristofferson’s or Martin’s best? Here’s a TV clip of them duetting on the song! (Kristofferson looks high, but is probably only drunk and wondering what the heck he’s doing in such a kitschy alternate universe.)

“Come Sundown” (1970)

Most country songs begin with the lyrics—or, more specifically, a single evocative phrase that suggests a lyric. A songwriter is almost never without a small pocket notebook in which to jot phrases like “Help me make it through the night” or “the fundamental things apply as time goes by.” From this kernel he or she develops the lyric, and only then does the tune come into play.

This song is different. It almost certainly began as a tune, with the lyrics fitted to it with some degree of difficulty: Note the four uses of the word “Lord” in a non-religious song that happens to need a few extra syllables to fit the tune.

The 1970 Bobby Bare recording is a good one, though I prefer Kristofferson’s own version (heard on Shake Hands with the Devil in 1979), done as a spot-on imitation of the great Ernest Tubb. The 1978 recording by Sen. Robert Byrd (D.-W.Va)—seriously!—has a nice bluegrass feel. A more conventional 1974 version by George Jones is a tad lugubrious for my taste, but has great soulfulness.

“Loving Her Was Easier (than Anything I’ll Ever Do Again)” (1971)

This Kristofferson classic is a great example of his love for long, looping lines—instead of the six-to-12-syllable lines of a typical country song, “Loving Her Was Easier” gives us 17. And each line is a poetic gem.

I particularly enjoy “wiping out the traces of the people and the places I have been,” because it expands into “wiping out the traces of the people I have been and the places I have been,” and I love the idea that the touch of his lover’s fingers erases the false identities he’s worn in the wider world: Only in her arms can he really be himself. (And the sadness, of course, is that he’ll never be there again.)

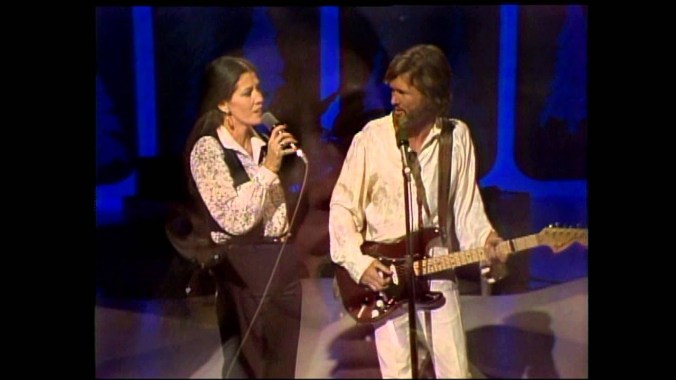

There’s quite a history of this song being done as a male/female duet, including a Kristofferson recording with Rita Coolidge and one of the two songs in his final public performance in 2023, alongside Roseanne Cash. These make no sense at all to me: If ever there was a song that calls to be sung by a single singer alone, this is it.

OK, so there are a lot of possibilities here. The essentials are the Waylon Jennings original recording and the Kristofferson version, both from 1971. The Kristofferson is beautifully sung, but I find Foster’s Nashville Sound arrangement, with lush strings and muted drums, excessive; I prefer the simpler performance by Jennings. I’d advise skipping the rhythmically perverse, Nashville Sound version by Eddy Arnold, likewise from 1971.

The first of a good number of gender-flipped “Loving Him Was Easier” adaptations was also from 1971, featuring Anita Carter, who may have had the best voice in the history of country music. And, for those who inexplicably like the duet versions, here are Kristofferson and Coolidge, from 1978, singing “Loving You Was Easier.”

“Jody and the Kid” (1968)

Like any Kristofferson song, “Jody and the Kid” offers a virtual clinic in songwriting technique, as he characteristically avoids the easy answers to conventional challenges in favor of innovative choices of his own.

Right from the start, Kristofferson makes things hard on himself. It’s challenging enough to tell a story spanning maybe 20 years, and to do it in only six sentences covering only 24 lines. But Kristofferson is just getting started: His story will be divided into three verses, each a genre song in its own right, and each verse will have a tone all its own. The first verse is essentially humorous, a story of a young man who is annoyed (but secretly pleased) by a little girl who tags along after him; the second verse is a love song; and the third verse is—like almost all of Kristofferson’s great songs—a story of loss and loneliness.

There’s nothing in the first verse to warn us what will happen in the second verse, and nothing in the second verse to warn us what will happen in the third. Each verse has different goals to accomplish, and only eight lines—only two sentences!—to do it in. And each has to end with the same four words, “Jody and the kid.”

The obvious first line would be something that would set up the central relationship—say, “She was 9 and I was 13.” But Kristofferson hates opening with the obvious. He likes to drop us into the middle of a story, with a line that in itself tells us nothing of the who, what and why of the situation: “Take the ribbon from your hair” or “Busted flat in Baton Rouge and headed for the trains.” He trusts his listener to follow a trail of breadcrumbs to achieve understanding.

The opening line, “She would meet me in the morning, on my way down to the river,” is a masterpiece, both misleading and revelatory. In the conventions of country music, “she” is always a romantic interest—which is not the case at all in Verse 1, but we’ll discover in Verse 2 that it actually is.

Having created this intriguing confusion, Kristofferson’s challenge is to lay the breadcrumbs to get the listener to where he wants to go. The third line, “with her feet already dusty from the pathway to the levee,” tips us off that this isn’t likely to be a romantic interest—that’s not the sort of thing that people say in country songs when talking about a lover. And then the fourth line, “with her little blue jeans rolled up to her knees,” tells us that this is a child—“little” is, of course, the key word.

The next two lines nail down the relationship (“I paid her no attention as she tagged along beside me,/trying hard to copy everything I did”), and then the final two lines tell us how he feels about that relationship (“but I couldn’t keep from smiling when I’d hear somebody saying,/’Looky yonder, there goes Jody and the kid.’”).

Kristofferson has already accomplished a huge amount in eight lines, and the real miracle of the song is that he’s going to do the same thing all over again in the second verse and then again in the third. One of these days I may write a full blog post just taking apart this masterful lyric, as I did recently with Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee” (1969); for the moment, why don’t you look for yourself at how he resets the story with each verse, at how in the last two lines of each verse he homes in on the singer’s emotions, and how in various structural ways he weaves these three episodes together? If you’re anything like me, you’ll be amazed.

I don’t always think Kristofferson is America’s greatest songwriter—there are plenty of other brilliant contenders for that crown—but I think it quite often

Three versions for you here; Roy Drusky’s original recording from 1968, all pear-shaped tones and tinkling piano, with all the Nashville Sound trimmings; Kristofferson’s own version from 1971, stripped-down and straightforward, and a surprisingly effective 1968 version by, of all people, George Burns, even more Nashville Sound than Drusky’s, but with more personality. (Burns’ age, very obvious in his performance, adds greatly to the interpretation.)

“I’d Rather Be Sorry” (1967)

This lovely song is a relic of Kristofferson’s early years in Nashville, when he was tempering his own instincts as a writer in an effort to make his songs more salable to Nashville’s mainstream artists. There are still some Kristoffersonian elements, notably the sensuality of the second verse’s description of the bed, but the emotions are simpler, less complex than will be his style later—questions about why she’s leaving, whether it was because of him and other, subtler issues aren’t addressed.

The melody is a lovely one, though, and there are several excellent recordings. Marijohn Wilkin—recording as Romy Spain in 1967—delivers a gentle, rather mannered version that introduces some odd syncopation. The Ray Price 1971 version is much more florid, and packed with Nashville Sound overkill, but still messes with the song’s rhythm’s and doesn’t capture the sense of wistful advance regret that characterizes the later versions: The Kristofferson/Coolidge duet from 1974 is much better, proving that less is more, at least where Kristofferson songs are concerned; Kristofferson never recorded a solo version in the studio, but this live version from 2014 (40 years after he duetted with Coolidge) finds the aged singer’s wistful voice well suited to the material. Then there’s a drifting Statler Brothers version from 1972 has beautiful harmonies and the subtly comic undertone that informs all of the Statler’s work.

The best recording of this oft-recorded song, however, may be this lovely one by the great Anita Carter, recorded in 1971 but inexplicably not released until 2004. I hope Kristofferson heard it.

“How Do You Feel (about Foolin’ Around)” (1978)

Because Kristofferson performed this rollicking song with Willie Nelson on so many occasions, including the movie Songwriter and various live performances with the Highwaymen or on their own, many people think that Nelson wrote or co-wrote it. In reality Kristofferson’s co-writers were guitarist Stephen Bruton and keyboardist Michael Utley, presumably because their work on the recorded arrangement contributed so much to the song.

It’s been recorded by various other people, but the key performances are still Kristofferson’s solo version from Easter Island; the Nelson/Kristofferson version from the Songwriter soundtrack; and the Highwaymen tearing it up. Each has its own rowdy charm.

“Daddy’s Song” (1981)

This song was a new experiment for Kristofferson, who had rarely if ever written songs that were identifiably about himself and his family. It wasn’t hard to connect the dots between the narrators of “Sunday Morning Coming Down” or “Help Me Make It Through the Night” and Kristofferson himself, but only in general terms; the connection between him and the narrator of “Daddy’s Song” is clear and unmistakable.

This may be why, unlike most Kristofferson songs, this one has never been covered by any other recording artists. Aside from a few live performances, his original version stands alone.

“A Moment of Forever” (1994)

There’s a serenity to this song which is remarkable in the context of Kristofferson’s overall body of work. He was a brilliant and complicated man who never stopped thinking and who had an allergy to simple answers, and most of his songs are masterpieces of ambivalence.

The word “forever,” in particular, is almost always used ironically in his work—but here it’s used sincerely. After a quarter-century of songs that treated love as fleeting, transitory or transitional, Kristofferson is now convinced that he’s found something that has lasted and will last. As for him, he’s finally “old enough to learn something new.”

Here are three versions for your consideration: Kristofferson’s beautiful, definitive original, with Danny Timms on piano (better than I could ever be) and Jimmy Powers on harmonica. Timms co-wrote the song. Willie Nelson’s version lacks the flowing beauty of the Kristofferson recording, but he’s a graceful and sympathetic singer. K.T. Oslin offers a simple, gentle reading much in the spirit of Kristofferson’s original, with (for some reason) slightly altered lyrics.

“Sunday Morning Coming Down” (1969)

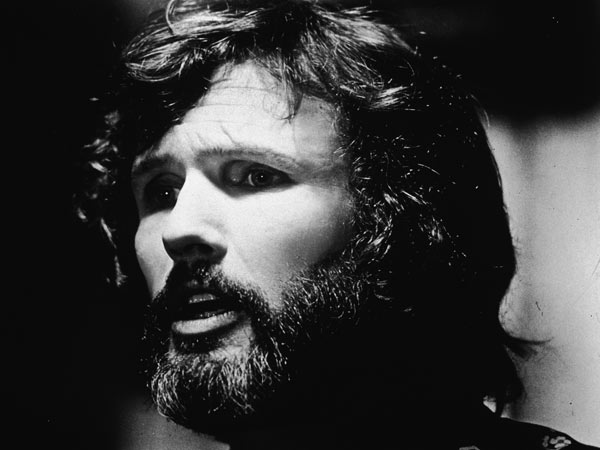

One of the great stories from country history relates to this song. It’s been told many times and doubtless embellished; even the two people most prominently featured in it had different recollections of it in later years. That said, at least the outline of what follows is the truth.

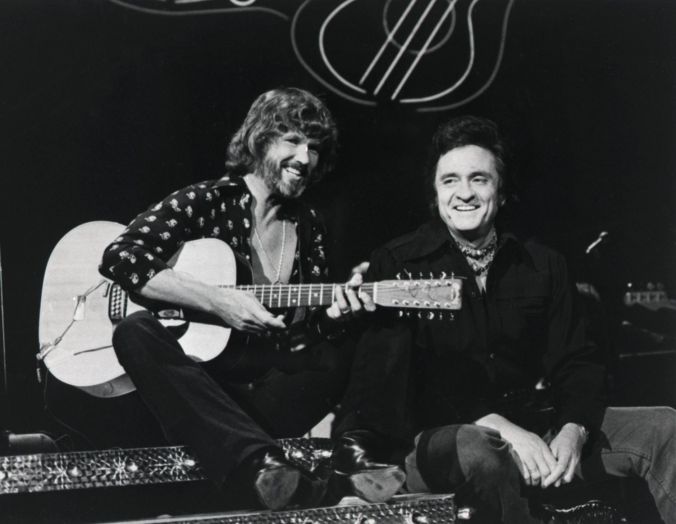

One day in early 1969, Johnny Cash and June Carter were sitting on their porch in Henderson, Tennessee, enjoying a pleasant morning by the lake, when they heard a noise that didn’t fit in. Looking up, they saw a helicopter passing overhead. Except that it didn’t pass: Instead it descended and landed on their lawn. The pilot hopped out and came up to the house, and Cash recognized him as one of the janitors at Columbia Records’ studio in Nashville. “Mr. Cash, hey,” he said. “I’ve got a song here I think you should listen to.”

Now, this was before John Lennon’s murder in 1980, and celebrities were more open to the approach of strangers, but it was still a pretty unusual thing. And country stars are constantly being passed demos (cassette tapes then, CDs or digital files now), which they usually discard unheard for fear of subsequent charges of plagiarism. (Cash was in the habit of chucking them into the lake.) But the sheer boldness of this guy’s approach amused Cash, who was always something of a rebel, and he agreed to listen to the tape.

This story would be a weird little “oddities of being famous” story, except that the pilot was the then-unknown Kris Kristofferson, and the song was “Sunday Morning Coming Down.” Cash recorded it later that year, and played it on his nationally broadcast Johnny Cash Show on ABC, and Kristofferson was on his way. By the next year he’d been voted Songwriter of the Year at the Country Music Association Awards.

Now, that’s the way that Cash recounted it, except that he said that Kristofferson had a tape in one hand and a beer in the other—which Kristofferson denied, noting that it takes two hands and one foot to fly a helicopter, and he should know. Kristofferson also insisted that the song in question was not “Sunday Morning Coming Down,” but a different one that Cash never recorded. That may be because—according to June Carter Cash, who was there—as soon as Kristofferson returned to the sky, Cash chucked his tape into the lake with all the others.

Details aside, the basic facts are that Kristofferson had been trying to get Cash to listen to his music for months, without success. A retired Army captain, Kristofferson was in the Army National Guard, and had periodic duty stints to keep his skills current—including his certification as a helicopter pilot. Up in the sky over Tennessee that morning, it occurred to him that he knew where Cash lived, and that an in-person delivery out of the blue might catch his attention.

One way or another, it did. The two men became close friends, fellow band members and frequent collaborators until Cash’s death. It was Cash who lobbied for Kristofferson to be invited to the 1969 Newport Folk Festival, which launched his career as a performing artist.

There are many, many versions of this I could put forward (Nicol Williamson? Telly Savalas? Carroll Baker? They’re all there … ), but let’s take Ray Stevens’ strangely jaunty original version from 1969, and then a Highwaymen foursome: Johnny Cash’s definitive live version in 1969 (notice his looking left to make eye contact with Kristofferson, sitting in the audience, as he sings the conroversial word “stoned”), Kris Kristofferson’s impeccable performance in 1970, Waylon Jennings’ swinging version from 1971 and Willie Nelson’s long, slow performance from 1971. Or, if you prefer, the Highwaymen as a group (a group song about loneliness!) in a live performance from 1990.

“The Silver-Tongued Devil and I” (1971)

Yes, there really was a Tally-Ho Tavern (great name for a place to chase women), but it wasn’t called that. During his pre-stardom years Kristofferson worked there as a bartender, and was also a regular customer. His drinking in those days was considerable, as was his womanizing, both of which are referenced in the song.

One of the things I love about this song is the way it doesn’t hit you over the head with what it’s about. Kristofferson, having majored in English literature, was undoubtedly familiar with “The Secret Sharer” (1909), a famous short story by Joseph Conrad which may have inspired this song. It follows a similarly oblique path.

I had some trouble learning this song—my lips kept saying “the silver-haired devil,” even when my brain was getting it right. Those who’ve seen me may be able to understand this error. Fortunately, the years have solved that problem, and my particular devil is now snow-haired.

Anyway, here’s Kristofferson singing the song in its original recording. Classic, both for the song itself and also for his ruefully humorous performance. It’s been covered only a handful of times (included by Shooter Jennings, Kristofferson’s artistic nephew), but none have rivaled the original.

“Broken Freedom Song” (1974)

Thid song is one of a number in which Kristofferson, known as “the Bard of Freedom,” ponders the cost of freedom … and, at least in this case, finds it wanting.

The unifying element for its depiction of three disparate people—a disabled soldier in the first verse, a single mother-to-be in the second and Jesus awaiting crucifixion in the third—is that they are alone, free of ties to others but none the better for it. Each has been abandoned, in his/her own way, and in describing them the word “freedom” is always used ironically.

It’s interesting, but ultimately futile, to speculate as to whether the lines about Jesus wondering “why his father/left him bleeding and alone” has any resonance with Kristofferson’s own status as a disowned child.

Here’s Kristofferson’s own version, from Dispossessed, and Roseanne Cash’s 1974 performance from Johnny Cash’s album The Junkie and the Juicehead Minus Me (which omits the first verse).

“They Killed Him” (1986)

By the time Kristofferson got around to recording his own version of this angry song, it had already been covered by two iconic singer/songwriters: Johnny Cash made the first recording in 1984, bringing characteristic gravitas to the song (along with a couple of tiny lyric changes) but also a certain disengagement; Bob Dylan’s 1986 version is all over the place, but has a sort of ritualized power to it. Both Dylan and Cash use children’s choruses, and they sound similar; I don’t know if they were the same, though.

“Third World Warrior” (1990)

Predictably, given his background, Kristofferson’s album about the fighting in Nicaragua focuses not on the leaders of the Sandinista cause, but on the men (and women) actually doing the fighting. It rises steadily through three keys to give the song dynamism, as do the powerful electric-guitar parts that aren’t really replicable for one guy on one piano!

Here’s Kristofferson’s own recording; other than a few live performances by him, it’s the only version.

“Best of All Possible Worlds” (1969)

It’s been said that this song is based on an actual incident in Kristofferson’s life, but it’s unlikely. Hippies were routinely hassled by police officers, especially in the South, and arrested for drug possession, vagrancy or other easily cooked-up charges … but Kristofferson wasn’t a hippie. He moved to Nashville at the age of 29, well outside of the usual age to be targeted by police, and before that time he was generally in uniform. Even after leaving the Army, he wore his hair short for some years, and didn’t roam the country—he had a wife and kids to support. The song was probably inspired by stories he’d heard from younger, hippier friends.

Roger Miller made the original recording, which is bouncy and fun, but lacks the sardonic edge of Kristofferson’s own recording, which came out less than a year later.

“Little Girl Lost” (1972)

William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience includes a poem called “The Little Girl Lost” (and also one called “The Little Girl Found”). Blake (1757-1827) was fascinated by the ideas of innocence and experience, which for purposes of this song we can define as simple moral purity and as the moral compromises necessary to function in the human world. He viewed prostitution—which was a major social problem in 18th– and 19th-century London—through this lens, as Kristofferson does in this song.

The perspective of the song defines ambivalence: The verses define the prostitute as heartless, calculating and dangerous, but the chorus sees through her to the lost little girl inside her, and insists on seeing her as a human being. The jagged, sharp-edged music and lyrical imagery of the verses invoke deceit, treachery, betrayal, manipulation and even amputation, while the music and lyrics of the chorus are simple, declarative and soulful. (Note, though, that the lyrics represent her also as lost, looking for a home and pleasing for help; this is not a person viewed as two different people, but two sides of the same person.)

The backstory is deliberately left unclear, which is uncharacteristic of Kristofferson. The obvious interpretation is that the prostitute is the narrator’s former sweetheart; for myself, keying off of the words “little girl,” I read him as her father.

Either way, it’s a disturbing song, both musically and lyrically, and a world away from conventional country music, in which prostitutes appear fairly often, but rarely if ever are treated with such emotional turbulence.

Here’s Kristofferson’s blistering original; there are no major covers, which isn’t surprising.

“Here Comes that Rainbow Again” (1982)

This one is based on a scene from John Steinbeck’s classic novel The Grapes of Wrath (1939), made into an equally classic movie by John Ford the next year. As mentioned, Kristofferson had a degree in English literature, and a number of his songs draw inspiration from literary sources that might escape the notice of the average country fan.

This is one of my favorite Kristofferson songs, with a powerful evocation of human solidarity and compassion that’s rare in his work. It literally brings tears to my eyes—it took hours of rehearsing before I could get through it without breaking down.

Here’s Kristofferson’s own version; Cash’s version; and an odd-but-appealing video clip in which the maker has superimposed the Kristofferson recording on stills from the scene as it appears in Ford’s movie.

“I Hate Your Ugly Face” (2009)

There’s not a lot to be said about this song, except that any song which includes the words “you sorry-looking mess” can’t be all bad.

Understandably, given its origins, the song hasn’t spurred a lot of professional covers, but YouTube is filled with amateur versions—of varying quality, of course.

Here’s two versions by Kristofferson, his original 2009 recording and a live performance on Ralph Emery’s television shows. And, just for kicks, a fun version by the Kristofferson tribute band Rocket to Stardom.

“To Beat the Devil” (1970)

Here, as in “Little Girl Lost,” “The Silver-Tongued Devil and I” and numerous other songs, Kristofferson writes of the devil in a very specific way: For him the devil is the voice in our heads that tells us not to bother, not to try, to give up and take the easy way out. He’s the opposite of every human achievement.

I’m glad to know this, because it provides a context in which to make sense of the spoken introduction to this song on Kristofferson, in which he talks about meeting Johnny Cash in a studio hallway and realizing that he was “about a step away from dying,” and having that experience inspire the song.

Otherwise the connection between a drug addict on the verge of death and the temptation to give up an unpromising career doesn’t seem to make much sense. I think Kristofferson’s explanation would be that different people have different dark voices in their heads that keep them from achieving their goals: In his own case, the temptation is about doing nothing rather than tackling something that seems fated to fail; in Cash’s, the voice said “Let’s get high.”

This lesson may have escaped Kristofferson, since his own dark voice didn’t seem to tell him to give up rather than battling the odds, a battle that he’d long since committed himself to; his voice said, “This will be easier if you get drunk.”

Here’s Kristofferson’s original version, which wasn’t the first version. Ironically, it was Cash himself who made it to record shops first, in January 1970, five months ahead of Kristofferson’s. I like Cash’s version, which is well sung, but it lacks the ruefulness of Kristofferson’s.

For Highwaymen completists, here’s Waylon Jennings’ version, from his 1972 album Good Hearted Woman. It’s also very good. So far Willie Nelson hasn’t covered the song, but he’s still around and singing, so who knows?

“If You Don’t Like Hank Williams” (1973)

This is way more complicated than I ever realized.

To begin with, here are the lyrics of this song as Kristofferson recorded them in 1976:

I dig Bobby Dylan and I dig Johnny Cash,

and I think Waylon Jennings is a table-thumping smash!

Hearing Joni Mitchell feels as good as smoking grass,

and if you don’t like Hank Williams, honey, you can kiss my ass.

(Chorus) Because I think what they’ve done is well worth doing

and they’re doing it the best way that they can.

You’re the only one that you are screwing

when you put down what you don’t understand.

I dig Roger Miller, Merle Haggard and George Jones,

Shotgun Willie Nelson and those rocking Rolling Stones,

Anything them Eagles do is better than their last,

and if you don’t like Hank Williams, honey, you can kiss my ass.

(Repeat chorus)

OK, so far so good. And here are the lyrics as I perform them:

I dig Bobby Dylan and I dig Taylor Swift;

I think Eminem has a genuine lyrical gift.

Hearing Joni Mitchell feels as good as smoking grass,

and if you don’t like Hank Williams, honey, you can kiss my ass.

(Chorus) Because I think what they’ve done is well worth doing

and they’re doing it the best way that they can.

You’re the only one that you are screwing

when you put down what you don’t understand.

I dig Lady Gaga, Alan Jackson and Norah Jones,

Shotgun Willie Nelson and those rocking Rolling Stones.

Listening to K.D. Laing is a seminar in class,

and if you don’t like Hank Williams, honey, you can kiss my ass.

(Repeat chorus)

I dig Dolly Parton and Idina Menzel, true,

Paul McCartney, Beyonce and of course Dwight Yoakam too.

Anything by Nickel Creek is better than their last,

and if you don’t like Hank Williams, honey, you can kiss my ass.

(Repeat chorus)

I love Gilbert and Sullivan and Kris Kristofferson.

Anything them Chicks put out has a shot at Number One.

Love the Metropolitan Opera and I love the Canadian Brass,

But if they don’t like Hank Williams, honey, they can kiss my ass.

(Repeat chorus)

As it turns out, however, the history of the song is far more muddled than I have time to sort out in the couple of days that I have available to me at this writing.

“If You Don’t Like Hank Williams” was originally recorded not by Kristofferson in 1976, but by British country singer Frank Yonco back in 1973; I can only assume that he somehow ran into Kristofferson or vice versa (maybe knew his Oxford connections?), and ended up licensing the song for a British recording that isn’t available anywhere, so far as I can tell. (Yonco and Kristofferson are both deceased, so the answer is probably lost in the swirling winds of time.)

The second recording, in 1975, was also by a pair of British artists, Cal Ford and “Rev” John White; Ford was apparently nicknamed “the Welsh Johnny Cash.” Here’s their version, with a different assortment of names. Is this an early version of Kristofferson’s song, or did they adapt it as they saw fit? I have no idea.

And here’s Kristofferson’s recording, which introduces the fusillade of shout-outs at the end. Visit this page again in May 2025, and I’ll provide a list of all the people named in the shout-outs (too pressed for time to do it now, with this show opening on 5 April).

Hank Williams Jr. did a reasonably enjoyable version in 1980 which sticks fairly close to the Kristofferson, though falling a bit short.

Winning the prize for missing the point is the 1976 recording by Rayburn Anthony, which replaces all of Kristofferson’s non-country names with country names: “I dig Bobby Bare … ”

“Rocket to Stardom” (1975)

Kristofferson brings a dark, sardonic humor to most of his songs, but he’s written very few overtly comic songs, ones whose primary purpose is to amuse and entertain. His sense of personal bemusement at the Hollywood lifestyle comes through loud and clear.

Which is not to say that this song is autobiographical. It’s likely at least as much inspired by stories he heard from other Angelenos than from his own personal experience.

But who says that a country song has to be autobiographical?

Here’s Kristofferson’s recording, which is the only extant one. (For some reason the record company has not posted this track on YouTube, so this modestly amusing video is the only version available; if you don’t like the video, simply listen to the music while looking at something else.)

“This Old Road” (1986)

Kristofferson recorded this lovely song twice, in 1986 for Repossessed and in 2006 as the title song for This Old Road. I like both versions—his voice was certainly in better shape in 1986—but I prefer the aging-but-not-world-weary tone of the 2006 recording better.

It’s got a beautiful balance of regret and tranquility, love and sorrow. As I age myself (at this point, I’m closer in age to the 70-year-old Kristofferson than to the 50-year-old version), I find this more and more evocative. Lines like “Nothing’s simple as it seems,” “traces of a future lost” and “thinking of the faces in the window” speak to me and, I imagine, to anyone who’s come a ways down the road, but hopes to go a bit further yet.

As a bonus, here’s a music video for the 2006 recording. I keep waiting for Kristofferson to check his Fitbit (he’s certainly not concentrating on his lip-syncing), but it still is picturesque and strangely moving.

“Mama Stewart’s Eyes” (2013)

This songs, deeply emotional but also deeply thoughtful, is one of the most moving songs I know, with Kristofferson stripping down his lyrics to the bare bones to talk about someone he knew only briefly, but who made a big enough impression on him that, 40 years later, she was still in his mind and heart. All of that is right here in the song.

Mama Stewart was half Scottish and half Cherokee, and was also a folksinger who preserved songs from both halves of her heritage. If you’d like to hear her and even see pictures, listen to “I’ll Turn My Radio On,” by the folk group Walela, made up of sisters Rita and Priscilla Coolidge and Priscilla’s daughter Laura Satterfield; the first voice you hear is Mama Stewart. Check it out—you’ll be glad you did.

“Why Me?” (1972)

In Kristofferson’s entire career as a recording artist, he had only one No. 1 country hit, and this is it. It also spent 19 weeks in Billboard’s Top 40, peaking at No. 16. I love Kristofferson’s performance of the song, which he’s used as the finale for every one of his shows that I’ve ever seen.

The best performance of it that I’ve heard, however, came in 2017 when I was in Nashville to see The Grand Ole Opry. Gospel singer CeCe Winans was a guest artist, and she had no business being there—not because she’s a Black woman, but because there’s nothing country about her. She didn’t announce the song, just said that it was “one of my favorite songs I’ve ever heard,” but she kicked into this song and pretty much lit the house on fire—cowboy-hatted country lovers swayed back and forth, sang along and, when it was over, responded with the biggest roar of approval that I’ve ever heard outside of a Taylor Swift concert. Truly a memorable night.

Here’s Kristofferson’s indispensable recording, and here’s Winans’ terrific cover. (Sadly, that live performance isn’t online in a complete form, but this captures the music, if not the power of the moment.) And, to put a bow on it, here’s Kristofferson telling the story of how he came to write the song. (Yes, the bored-looking guitarist is Willie Nelson.)

And two bonuses: A tuneful (albeit unduly choppy) recording by the great Merle Haggard, and the equally great Connie Snith going Gospel to great effect. Neither is as on-the-money as Kristofferson or Winans, but a great song can live in many forms.

“Me and Bobby McGee”

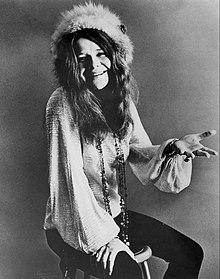

“If it sounds country, man, that’s what it is. It’s a country song.” So says Kristofferson in a verbal aside leading into his 1970 recording of this song.

It’s as if he was able to see the future and anticipate that many people would come to think of his song as a rock song, thanks to Janis Joplin’s 1971 recording, which was her first and only No. 1 pop hit. But Kristofferson didn’t even know that recording existed until after Joplin’s death in 1971, so that wasn’t what he was talking about. He may have been discussing some other recording of the tune that preceded his—say, the poppified 1969 version by Kenny Rogers and the First Edition. Or he may have been talking about some unrelated song, or even about musical philosophy in general. (His comments are a key reference in the ongoing, never-to-be-resolved debate about what country music really is.)

If he was talking about his own recording, well, yeah, that’s definitely country. But like any truly great song, “Me and Bobby McGee” has been cast into various different modes, and its greatness comes through in … well, in most of them.

Hundreds of possibilities here, so let’s go with five more options, four of them obvious and one less-than-obvious: Here’s Roger Miller in the original 1969 recording—still a very good one; here’s Kristofferson singing his own song in 1970, as a slow, meditative country ramble; here’s Janis Joplin with her iconic 1971 recording, and a typically high-energy, Cajunized version from Jerry Lee Lewis. And, just for giggles, here’s Jennifer Love Hewitt going all emo and whispery, for some reason.

I could say more about this song, but I already wrote a whole blog essay about it, titled “Me and ‘Me and Bobby McGee,” back in 2020. Check it out!

“Please Don’t Tell Me How the Story Ends”

This beautiful song is, like most Kristofferson songs, about loneliness–in this case anticipated loneliness–it’s a somberer version of Faron Young’s classic “I Miss You Already (and You’re Not Even Gone),” from 1957. The song took awhile to find its footing. Bobby Bare’s 1971 recording made no impact in the marketplace, nor did a Ronnie Milsap recording from later that year. In 1974, however, Milsap took a second bite from the apple, and this time hit No. 1 on the charts.

Kristofferson himself didn’t get around to recording it until 1978, when he and his then-wife, Rita Coolidge, recorded a duet version. Given the subject matter, it perhaps shouldn’t be surprising that they divorced the next year.

Here are four versions for your consideration: Bare’s original version, from 1971, with a sauntering cowboy beat that doesn’t seem to me to fit the song well; Milsap’s hit version from 1974, which is closer to my own sense of it, but features some classic Nashville Sound overproduction, especially at the end; the beautiful recording by Kristofferson and Coolidge from 1978, showing Coolidge’s world-class voice to good advantage, but also some unintentionally comic burbles in the arrangement; and, finally, my favorite version of the song, from 1999, with an aging Kristofferson singing it simply and directly.

In recent years Kristofferson sang this song more often, sometimes using it to close his shows. I think his sense of the song evolved as time passed, from a song about relationships to a song about mortality, directed not from him to a lover but from him to his audience.