Reviewing I Walked the Line: My Life with Johnny, by Vivian Cash

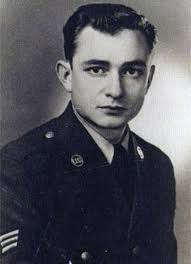

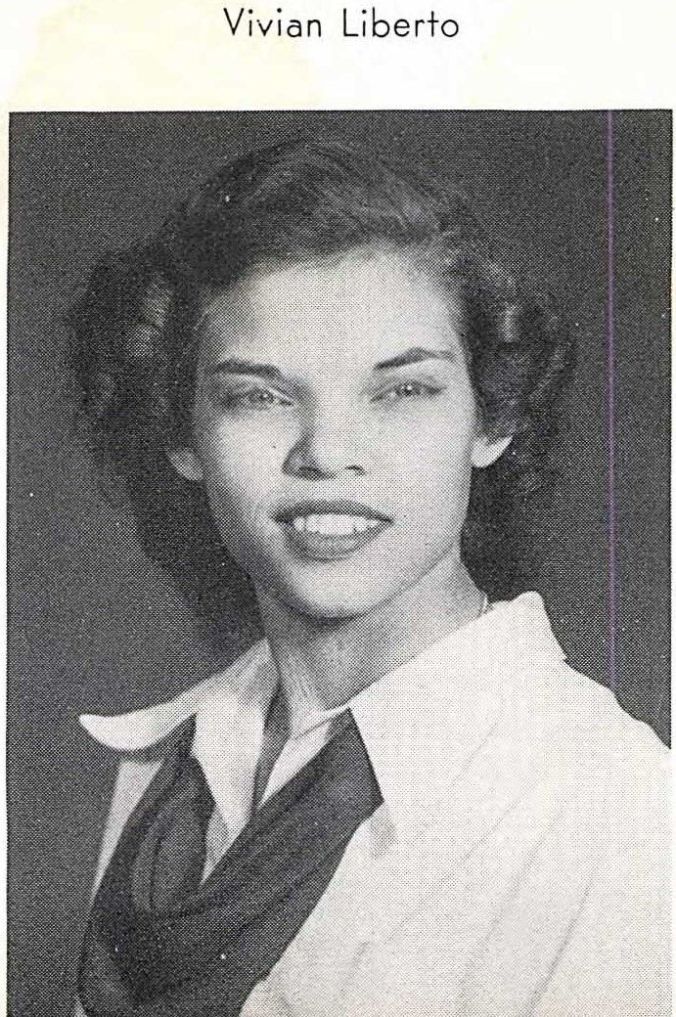

At first glance, it’s remarkable that I Walked the Line: My Life with Johnny is seldom drawn upon by the constantly swelling ranks of authors writing books about Johnny Cash. After all, Vivian Liberto Cash Distin (referred to hereafter as “Vivian,” to distinguish her from her ex-husband) was there when it happened, as a famous Cash hit proclaims, and therefore she ought to know.

All the elements seemed to be in place for a substantial book that would offer a trove of previously unavailable information on the formative years of Cash’s career as a musician and on the man behind the image of the man in black. Besides Vivian’s unique perspective, her book was written and published after Cash and his second wife, June Carter Cash, were dead and unable to fire back, and at a time when Vivian herself was in failing health and, as a result, perhaps more willing to tell her story than at any previous point.

Nonetheless, when the book (co-written by Ann Sharpsteen) appeared in 2007, it made no great splash and hasn’t had much impact since.

Part of the fault may be Sharpsteen’s, or Vivian’s for choosing Sharpsteen. A freelance writer and producer for television, Sharpsteen is neither a scholar nor a substantial author (her only other book, from 2019, is titled How to Leave an Asshole). She met Vivian Cash while researching a Johnny Cash documentary for MTV Networks, and bonded with her: By her account and Vivian’s, they became close friends, and the book grew out of that friendship.

It’s natural that Vivian, who had never before written anything for publication, would feel more comfortable working with a writer with whom she had an existing tie. Had she sought out a professional, however—and, given who she was and the story she had to tell, she would have been able to do so—she might have gotten the advice that she needed to produce a book of lasting appeal. As it is, she ended up with a book which, both in content and in structure, is highly problematic.

Vivian had one thing that was unavailable to any previous writer on Cash—even to Cash himself, in two autobiographies written in 1975 and 1997. That was her collection of letters written to her by Cash during the years he spent in Europe, serving in the Air Force. These letters, spanning the period from September 4, 1951, to June 17, 1954, are a valuable resource to anyone interested in who Johnny Cash really was. They include assorted nuggets that cast light on later developments, notably including which songs Cash was listening to during the years in which he began his emergence as a musician.

However, the letters are highly repetitive, with the nuggets scattered here and there among a sea of less interesting material. I can say this with assurance because the book includes every one of them (so far as a reader can tell, anyway), uncut; many are reproduced photographically, in Cash’s strong, clear, printed script which is almost unfailingly easily legible. The book is 324 pages long, but only 68 of them are text by Vivian; a foreword and an afterword by Sharpsteen account for another seven pages, and the remaining 249 are taken up by Cash’s letters.

In other words, if Vivian had a book in her, this isn’t it. It could more accurately be titled The Letters of Johnny Cash, 1951-1954. Had Sharpsteen been concerned more with what the book should be than with giving her friend what she wanted, presumably she would have told Vivian that a book subtitled My Life with Johnny should be more than ¼ about that life; as it is, the book is basically by Cash, and should be subtitled My Life Without Vivian.

From a structural point of view, therefore, I Walked the Line is inevitably a disappointment. The share of the book written by Vivian and Sharpsteen is equivalent to a long magazine article; the rest of it is by Johnny Cash, and should have been credited accordingly. (The book also suffers from the absence of an index, making it difficult to track down those nuggets on second reference.)

This alone is not enough to make the book a disappointment. There are any number of fascinating long magazine articles (some of them about Johnny Cash), and Vivian’s unique vantage point might have produced enough compelling material to justify its publication, even if it wasn’t the 324-page exploration of “my Life with Johnny” promised in the book’s subtitle.

Unfortunately, I can say—speaking as a former magazine editor and as the entertainment editor for The New York Times Syndicate for more than a quarter-century—that Vivian’s contribution to the book (a 10-page introduction recounting how the book came to be written, a six-page “Part I” explaining the context of the letters and a 51-page “Part II” covering their 12-year marriage after his return from Europe) wouldn’t have passed muster with any competent magazine editor.

Half of good writing is to have a story to tell, and Vivian definitely has that: She wants readers to understand, first, that Johnny Cash was a good man who loved her passionately; second, that his good nature was undermined by drugs which warped his personality beyond reclamation; and, third, that he turned to drugs because a predatory woman named June Carter took advantage of his weakness to lure him away from the wife and four daughters who had been the center of his life.

This is a clear and dramatic story; unfortunately, Vivian’s account doesn’t make much of a case for it. The portrait of Cash that emerges is sharply different from the one she wants to deliver, and produces the impression that Vivian either is covering up the true story or simply didn’t really know much about the man she met when she was 17 and married when she was 20, after having spent only seven weeks with him (three before his departure for Europe, four after his return three years later).

As far as Cash’s loving Vivian, we have his word for it: We have it repeatedly, and usually in the same words: “Vivian, I love you.” The letters in Vivian’s book are, above all, love letters, and Cash seldom strays far from the refrain that he loves Vivian, misses her and longs for the day they can be together.

It’s not entirely his fault that his letters lack much else that’s of interest. His work as an Air Force radio operator was classified, so he could tell Vivian little about his job. Still, as an intelligent American making his first trip to Europe (mostly in Germany, but with brief visits to several other countries), he might be expected to offer far more descriptions of the people, places and customs he encounters.

Nonetheless, the letters do offer a revealing picture of their primary subject, which is not Vivian, but Cash himself: It could hardly be otherwise, because he hardly knows Vivian—they met three weeks before he left for Europe, remember—so he doesn’t have much to say to her beyond his professions of love. However, what he does say is interesting—and, if a friend were having such a correspondence with a soldier sweetheart, I’d find it alarming.

Cash is obsessed with Vivian’s fidelity or lack of same. He doesn’t accuse her of being unfaithful—on the contrary, he begins every complaint about her conduct (as he imagines it) by emphasizing that he knows she isn’t cheating—but nonetheless he’s alarmed by her getting a job, concerned about her male co-workers and upset by her going out with female co-workers to clubs or bars. He makes no secret of his skepticism about her female friends, and implores her not to associate with them because they all strike him as people of bad character who will drag Vivian down with them. (It’s hard to be sure how much of this comes from him and how much from Vivian, since she includes none of her own letters and Cash rarely explains specifically what he’s talking about.)

He also writes repeatedly about the other airmen he lives and works with—about how many of their sweethearts at home have turned out to be unfaithful and about how many of his comrades are themselves cheating. He explains so heatedly that he never even looks at the German girls, whom he refers to most often as “pigs,” that it’s hard to know whether he’s protesting too much or is actually physically repelled by any woman who isn’t Vivian (or at least Vivian as he imagines her).

Cash’s particular horror is the idea that Vivian may be drinking. Though he isn’t converting to Catholicism, he has agreed to respect her Catholic religion, to marry in a Catholic service and to have their children brought up as Catholics. He seems to regard her Catholicism as unusual but not especially significant—he’s not particularly religious during these years—but her being Catholic does trouble him in one regard.

He’s not worried about the Pope, about anti-Catholic prejudice, about the prohibition of birth control, the ban on divorce or any other doctrinal aspect of her faith: He’s worried that Catholic culture accommodates “moderate drinking,” and he’s convinced that this will destroy Vivian and their marriage: “Honey tell me the honest truth do you believe in moderate drinking, and do you have any desire to drink?” Again and again, he asks her to agree to abstain entirely from alcohol, even in small amounts, and her apparent refusal to do so vexes him greatly.

This reads strangely alongside another aspect of the letters: Cash is constantly vowing to forego alcohol himself, only to guiltily admit to having gotten drunk; he doesn’t admit to having cheated while drunk, but will fess up to brawling, at one point almost going to jail for knocking out a civilian’s teeth. What he does repeatedly when drunk, though, is to write panting letters to Vivian in which he rhapsodizes about her purity, discusses her underwear (as he imagines it) in detail, offers fulsome tributes to her breasts and other body parts, and looks forward to their future sex life. These letters are invariably followed by abject apologies (“I don’t mean to be so hateful, and I know I owe you an apology”) and a vow to never again touch drink … a vow which doesn’t last for long, as the cycle starts again.

This obsession with alcohol leads to some interesting revelations of how little Cash knows about life outside of rural Arkansas. At one point, for instance, he asks her, “What is a wedding reception, and do we have to have one?” His concern, of course, is that he’s heard that people drink at wedding receptions, and this has alarmed him.

Overall, the picture of Cash that emerges from the letters is not that of a pining lover, but of a jealous, possessive, neurotic young man with an addictive personality, occasional violent tendencies and a strong desire to control his prospective wife. If my friend were considering marrying such a man, I’d encourage her to wait until they’d had a chance to get to know each other much better.

That isn’t what happened, of course. Cash returned to the United States in July 1954, and he and Vivian were married a month later. It is at this point that Vivian’s “Life with Johnny” actually begins.

Vivian’s take on what went on in their life together is simple: Her loving husband, who didn’t drink, mess with drugs or fool around with other women, became a major country singer/songwriter and everything was fine … until it wasn’t. From the moment she met June Carter, then recently married for the second time, she sensed a threat, Vivian writes:

“She thrust out her arm and showed me the ring on her left hand … “Look, with every husband, my diamond gets bigger!” she exclaimed.

For some reason that first encounter haunted me for years … I sensed an unspoken agenda. If she were the type of woman to judge a marriage by the size of a diamond, I thought, she would judge a man by the measure of his success. And Johnny was ripe for picking.

Vivian seems to have had no sense that her marriage was in trouble before June Carter came along. She attributes Cash’s use of drugs to Carter, and writes that, according to her daughters, Carter had major drug problems of her own. However, many different sources have alleged that Cash had numerous other women outside of his marriage, including two (Lorrie Collins and Billie Jean Horton, the former unrequited—she was 15—and the second not) whom Vivian identifies as close friends. And it seems certain that Cash’s use of pills originated in the mid-1950s, as it did for so many other musicians, as a means to stay awake during long nights on the road, and to sleep once they’d reached their destination.

Vivian acknowledges having heard the rumors about Cash’s drinking, his drug use and the other women, and toward the end of the book admits that there may have been truth to at least some of those rumors. But she was a young woman, only 18 when she was engaged and 20 when she was married, and besotted with her husband. She wasn’t on the road with him after his earliest career days—instead taking care of a growing family that ultimately included four daughters—and she didn’t believe what she didn’t see, or what she didn’t want to believe.

To an outside observer, there are warning signs aplenty in Cash’s letters.

There is, of course, no way of telling whether we can believe Cash’s repeated proclamations that he’s remained true to Vivian. I incline to think we can, if only because Cash is singularly candid in admitting his own frequent drunkenness—in fact, one of the things he does again and again is to get drunk and write letters that begin “Honey, I’m drunk again” or some such. If he cheated, it seems as if he’d immediately tell her and apologize profusely.

Nonetheless, his suspicions about her behavior while he’s overseas, whether or not they stem from a guilty conscience, are striking. She forgives his drinking again and again, but he’s constantly suspecting her of drinking, and he distrusts all the men she encounters as “having only one thing on his mind” and all the women she knows (few of whom he’s ever even met) as loose, alcoholic people who will lead her into sin: “Yes, darling, it’s 1954 now, the year when all our dreams are supposed to come true. There’s one thing that’s endangering all our precious happiness that we’ve counted on for so long. That’s drinking, and that crowd you mix with.”

She repeatedly tells him that she’s been true to him, and he doesn’t challenge her claims, but his suspicions are relentless: “Maybe Kate is of the 10% that remain a lady after being divorced. I hope so, but under the circumstances it doesn’t seem probable. Divorced, and in a G.I. town, living alone with no one to take care of her and advise her. She’d have to be a strong-hearted woman … Viv, what else could I think except that [Anna] was a second class girl when she came in cussing and bragging abut the beer she drank. One time like that was enough to set an opinion of her. Even if all she does is drink a beer occasionally and say “damn & hell,” you’re too good to be around her.

Aside from constant professions of his love, Cash’s favorite topic is how sweet and innocent and pure Vivian is: “Viv, I don’t know what you’ll think, but a lot of times lately I’ve thought of you as being like Mary Magdalene. I know you’re only human, honey, but you’re pure, your language is pure, and you’re so lovely. That will probably surprise you, darling, me thinking that of you, but it’s the truth. If nobody bothered you and you weren’t around drinking and dirty talk, and some of the people you have to be around, you’d be a saint. God put purity and holiness in your heart and body, and if you were treated right, you’d be another Mary, on earth.”

The combination of his conviction of Vivian’s immaculate purity and his suspicions of her behavior lead naturally into thoughts of violence: “I want you to tell me what kind of idea these people have about you, why they think you’re just anybody’s girl when you’re so clean and decent. If I were in San Antonio now two men would tell me something or get their brains blown out.”

There are ample signs, however, that his violence isn’t limited to hypothetical cases involving her. What it’s closely related is his drinking. He admits to being drunk when he gets into a fight with a Polish soldier and knocks his teeth our, and later tells Vivian: “I went to Munich yesterday about noon with another guy. I won’t lie to you honey, I got drunk. I got so drunk I couldn’t walk … I almost got in trouble over a girl. One came up and sat down by me and started begging me for drinks and money and I was ignoring her and she started calling me names. I hit her with the back of my hand and knocked her out of her chair flat on the floor. The Germans called the police … Darling, I didn’t touch a girl except the one that I hit, and that isn’t on my conscience a bit. She should have been hit.”

His drinking also brings out an ugly strain of racism: “Now, honey, don’t be hurt cause I’ve been drinking. Just beer and Willie and I are looped. Baby I’m going to tell you something and you can figure it out. I had 70 cents, darling. That’s 14 nickels, and they sell beer for a nickel tonight. I’ve got 15 cents left, so how many beers did I guzzle? Honey, some nigger got smart, and I asked him to go outside and he was too yellow. He thought he could whip everybody in the club but he wouldn’t even fight me. He’s [a] yellow coon.”

Again: ”We got a taxi and started back to the hotel at 1:00. We stopped at the train station for a few minutes and a Negro called me a bus driver … I called him every name anyone has ever given a Negro. The further he walked away, the louder I yelled, calling him ‘Coon,’ ‘Nigger,’ ‘Jig-a-boo,’ and a few others. I yelled for a full 30 minutes that I could whip any Negro that walked on the face of the earth. None showed up so we went to the hotel and went to bed after waking nearly everybody in the hotel with our noise.”

The general picture that emerges is of a young man who doesn’t know much of the world and whose views are those of the 1940s Arkansas farm boy he was until he joined the Air Force in 1950. (Vivian comes across as more sophisticated but still very young and poor at spotting red flags, a failing that didn’t end with their marriage.)

Occasionally, however, there are signs of the poetic songwriter, man of God and warrior for justice that Cash would become with the passing years. In late 1953, for example, he hears from his mother that his parents have decided to sell the farm he grew up on:

“I was walking back from supper tonight, and I started thinking about it … and I honestly got tears in my eyes. I thought I was going to cry out loud. I know it was silly, but that’s the closest I’ve come to crying in a long time.

“Every tree, stump, bush, or every square foot of that place has a memory for me. I remembered especially once when my brother Jack and I were so small. I couldn’t have been over 4, and he was 6. We carried a little tin bucket of drinking water to my dad who was over in the field plowing. We found an old rusty quarter lying on the ground, and we were so happy when dad said we could keep it for our very own.

“Every inch of that place makes me think of something different, something wonderful and precious that happened. I could walk over that place and think of things I’d never remember any other way. I can remember Roy and Louise and Jack and Reba so well when they were all kids. It’s even sweet to look back over the hard work I did there with them.”

To his own seeming surprise, Cash flourishes as a radio operator: Despite his lack of much formal education, he takes to the job, wins commendations for his work and rises from airman first class to finish as a staff sergeant.

Meanwhile he is slowly emerging as a musician. In 1951 he’s simply singing for his own enjoyment—”There’s a couple guys here that play the guitar, and we stayed up till about 3 oclock this morning singing hillbilly music”—but by 1952 he’s singing “hillbilly” songs at a March of Dimes benefit, taking requests at a dollar a song.

“I sang every song I know,” he reports to Vivian, “and some of them at least a dozen times … You heard Hank Snow’s song ‘One More Ride?’ They made me sing that so many times that I heard it in my sleep last night. And everybody I meet today calls me ‘Hank.’”

Later that year he sings “Shine On, Harvest Moon” and “In the Evening by the Moonlight” at an Air Force function, and gets a commendation for singing.

In 1953 he acquires a tape recorder, and also visits a recording company to make recordings for Vivian and for his mother. He apologizes for the quality of the recording he sends Vivian, blaming his nerves during the session, and assures her that he can do better.

By February 1954 he can write to Vivian: “I’m getting a little serious about my singing, honey. I think I’ve improved my voice since I’ve gotten this recorder. I guess it’s only natural. When I’m not working or sleeping, that’s about all I do, is listen to music or play it.”

It would be a long way from Lansberg, Germany, to Sun Records in Memphis, but his eyes were already turning in that direction. Vivian charts the early days of that trek, and there’s a real warmth in her memories of the year after their marriage, when Cash, bassist Marshall Grant, steel guitarist “Red” Kernodle and guitarist Luther Henderson would sit in Grant’s garage, practicing for hours as their wives sat in the kitchen, playing cards and rolling their eyes at their husbands’ foolishness.

It’s clear that, while Vivian cherishes her memories of Cash’s ascent to fame, her heart is in those early days. It’s tempting to read Cash’s letter of November 30, 1953, and wonder how things might have gone if Cash had gotten what he says he wants:

“I don’t ever want to be rich. I want us to live comfortable, but if there was a choice to take, I’d rather be poor than rich. I was always so proud that I was a plain country boy. When I’d see some big shot driving a new car, smoking a cigar, I’d automatically breathe a prayer of thanks that I was poor. My life’s ambition was to walk up to John D. Rockefeller and tell him rich people don’t go to heaven.”

If he’s gotten his druthers, millions of country fans would be the sadder for it, and Vivian and their daughters might have been the happier. Would Cash have been? We’ll never know.

.

.

A Note to Readers: I began this blog in 2016, planning to make it a lively source for fans of classic country (and whatever it is I play) to read about music, musicians and how I see the world of country. I kept to that plan for some years, writing some essays of which I’ve been quite proud, but then got away from it for a long time, writing books, directing operas and posting nothing but program notes—which were, admittedly, about music, musicians and how I see the world of country. People still seemed interested in what I had to say, for which I’m grateful, but I was still amazed and distressed to discover that I hadn’t posted a single essay since July 2023.

I’m back, though, and while I’m not going to be so foolhardy as to promise anything specific, I can say that I have every intention of posting more frequently going forward, even while still writing books, directing operas and posting program notes. Thank you for sticking with us, and I’ll see you soon.